🏷️ Categories: Memory

“The existence of forgetting has never been proven. The only thing we know is that memory may not be within our reach.” ~ Friedrich Nietzsche, Aurora, 1981

Our memories, the unwritten biography of our lives, are the home of the past, a private place only we can access. Memories constitute our identity, encompassing the good and bad events of our lives. Not remembering something from the past is like it never happened, but what happens when we remember something that never occurred? Yes, you read that right.

It’s astonishing to discover that human memory is even more fallible than we imagine. In fact, it’s possible to have false memories. It’s startling to hear people assert things that never happened, detailing these fictitious moments with unsettling precision. This is the story of the phantom yield sign and the hot air balloon ride that never existed.

Let’s talk about memories

To start, what exactly is a memory and how would you define it? According to Daniel Schacter, one of the foremost scholars of memory, memory is a combination of two parts: the cue and the engram. The cue is contextual stimuli that trigger the memory (places, smells, sounds, etc.). On the other hand, the engram is the content of the memory (Schacter, 1982).

For example, the scene from the day I went camping with my friends and we were in the forest gazing at the constellations. I will remember bits of that scene, although as we already know, we don’t always remember everything. The cues that can remind me of this moment could be the forest or a smell of burning wood similar to the bonfire we made, etc. These things can trigger memories we hadn’t recalled in a long time. However, there can be failures in retrieving both the engram (the scene) and the cues (associated stimuli).

The case of the STOP sign

An astonishing example due to its simplicity is the experiment of the car accident at a STOP sign intersection. The experiment involves showing a series of photos to subjects in which a red car crosses a street with a STOP sign at the end where it should stop according to the sign, but it ignores the sign and hits a pedestrian. After the accident, the car turns at the intersection and goes in another direction. It’s just a handful of slides, nothing more (Loftus et al., 1978).

Then they were asked about the yield sign at the intersection. Just with that question, people responded normally, as if the car had ignored the yield sign, leading to a modification of the memory, that is, the engram. Remember, there was a STOP sign, not a yield sign. Days later, people still remembered that the car skipped a yield sign. Just with verbal suggestions, we can modify memories. The most incredible thing is how fresh they had the memory…

This effect is called the misinformation effect, meaning, subjects remembered well what happened, but by asking incorrectly, in this case, about a yield sign, the new information distorted the memory they had (Challies et al., 2011).

We also do this to ourselves. Every time we remember something, the memory is altered. We are not like a DVD that can always play the same memory; we always reconstruct memories, and each time, we remember a slightly different scene. Incredible, right? Well, what’s coming is even better.

The hot air balloon ride that never happened

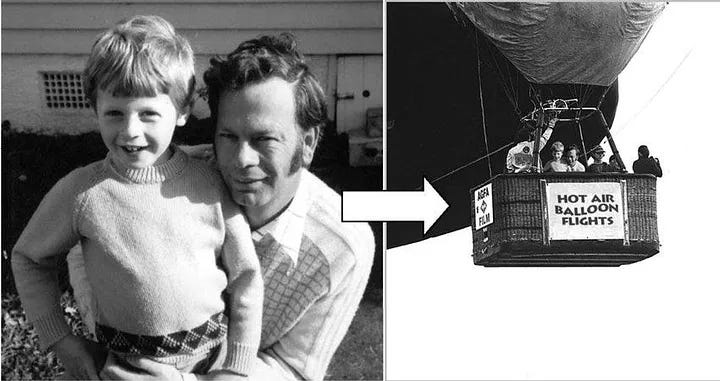

In this hot air balloon experiment, which is already a classic, participants were asked to look at photographs from their childhood. A family member of the participants had brought photos of them during their childhood. Without their knowledge, the researchers had made a graphic modification to create a fake photograph where the participant was traveling in a hot air balloon with their father. Then, they were interviewed about the childhood photographs, which included many normal photos and the fake hot air balloon photo (Wade et al., 2002).

The same experiment has been done on children with similar results; no one is exempt even when childhood memories are closer (Strange et al., 2007). Moreover, the same experiment has been done with texts, including the fake text about the hot air balloon, and the same thing happens (Garry & Wade, 2005).

In the first interview, people were asked about the experiences they had at those events, and to detail what memories they had of those photos, how that event was. Already in the first interview, 35% of the participants told the story of the hot air balloon as if they had experienced it along with the rest of the photos. They detailed all kinds of information about who took the photo, how the experience was, and more. Is it scary or not? Well, there’s more.

In the third interview, three weeks later, 50% of the participants already remembered the hot air balloon ride that had never happened as another memory of their lives. Half of the people included in their memory a memory artificially created by a group of psychologists. Anyway, it doesn’t take much; just by asking about a yield sign, we forget about the STOP sign.

Lessons learned

Memory is not a faithful reflection of the past by any means; it is an imprecise reconstruction of the past based on an engram (schema and bits of scene) that is also always biased by our own point of view and beliefs at the moment. It’s like making clay pots; a potter makes pots, they all look alike but none is the same as another, and none is perfect.

Your memories are too valuable to be lost or distorted in dusty corners of your mind. Capture your life through photos, videos, or a diary; in fact, this is what led me to start my journal.

I’ll tell you the story in more detail in this post:

Now that you know what false memories are, be careful next time someone tells you an experience that supposedly you both had and you don’t remember. Maybe it’s all a lie… 💭

📚 References

Challies, D. M., Hunt, M., Garry, M., & Harper, D. N. (2011). Whatever Gave You That Idea? False Memories Following Equivalence Training: A Behavioral Account of the Misinformation Effect. Journal Of The Experimental Analysis Of Behavior, 96(3), 343–362. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2011.96-343

Garry, M., & Wade, K. A. (2005). Actually, a picture is worth less than 45 words: Narratives produce more false memories than photographs do. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 12(2), 359–366. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03196385

Loftus, E. F., Miller, D., & Burns, H. J. (1978). Semantic integration of verbal information into a visual memory. Journal Of Experimental Psychology, 4(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.4.1.19

Schacter, D. L. (1982). Stranger Behind the Engram: Theories of Memory and the Psychology of Science.

Strange, D., Hayne, H., & Garry, M. (2007). A photo, a suggestion, a false memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology (Print), 22(5), 587–603. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1390

Wade, K. A., Garry, M., Read, J., & Lindsay, D. S. (2002). A picture is worth a thousand lies: Using false photographs to create false childhood memories. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9(3), 597–603. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03196318

Crows and other corvids have better memories than humans.

It might be that memory, for humans, is related to importance of events and whether there was human trauma, which either blocks the event or distorts it.

Back to the birds. The minds of corvids work in a different way than does the human mind. They have not been distracted by an artificial world that humans have. Such an artificial world, without a doubt, affects memory and our sense of reality.

An excellent memory experiment is to compare the effects of digital media on memory. To have a control group who rarely if ever uses such media. I suslect their memory would be better than any group that regularly is on the internet and in particular social and digital media.

I've had vivid dreams of flying (ala Superman) that I later remembered as having been a real happening.