Stanford University's $5 challenge for creatives and entrepreneurs

From $5 to $650 in 2 hours

🏷️ Categories: Mathematics, Creativity.

In 2009, Stanford professor Tina Seelig ran an experiment with her students…

Each team would receive $5 and have 2 hours to generate as much profit as possible. The following Monday, in a 3-minute presentation with just one slide, they had to explain how they did it. A tough challenge that demanded truly clever solutions.

What happened was remarkable.

The $5 Challenge

The challenge was born at Stanford University, inside an intensive course on entrepreneurial thinking. Professor Seelig wanted more than theory: she wanted to test her students and see how they would perform creatively under strict limitations, only $5 and 2 hours.

There were 14 teams, and each received a sealed envelope with $5 inside.

They had from Wednesday to Sunday to plan. But here’s the catch: the moment they opened the envelope, the clock started ticking, two hours to earn as much as possible. On Monday, in a 3-minute presentation with one slide, they had to explain their entire process of ideation, execution, and communication.

These were the best results…

Inflating tires: One team set up a booth in front of the student center: they checked tire pressure for free and, if needed, charged $1 for inflating. The value wasn’t the air, it was the convenience. Sure, there were free options for inflating tires, but none nearby.

Restaurant reservations: Another team noticed the endless lines at Palo Alto restaurants on Saturdays. They made reservations and resold them for $20 to people who wanted to skip the wait. They made a few hundred dollars.

But the real breakthrough came from the team that made the most money.

They realized the $5 was a distraction. They didn’t even use it. It was obvious that with $5 and 2 hours, there wasn’t enough capital or time to make a truly profitable investment. Instead, they thought differently.

“What if we never open the envelope and the 2-hour countdown never begins?”

That changed everything.

Selling the presentation time

This team saw that their most valuable asset wasn’t the $5 or the two hours.

It was the 3 minutes on Monday in front of an audience of Stanford students (highly sought-after talent for companies). They sold that presentation slot to a company interested in recruiting. $650. A return of more than 12,000% on the $5… which they never touched.

The secret wasn’t “working harder.” It was redefining the game.

And here comes the big lesson from this story (and how we can apply it)…

Breaking free from linear thinking

We often frame problems too narrowly and linearly.

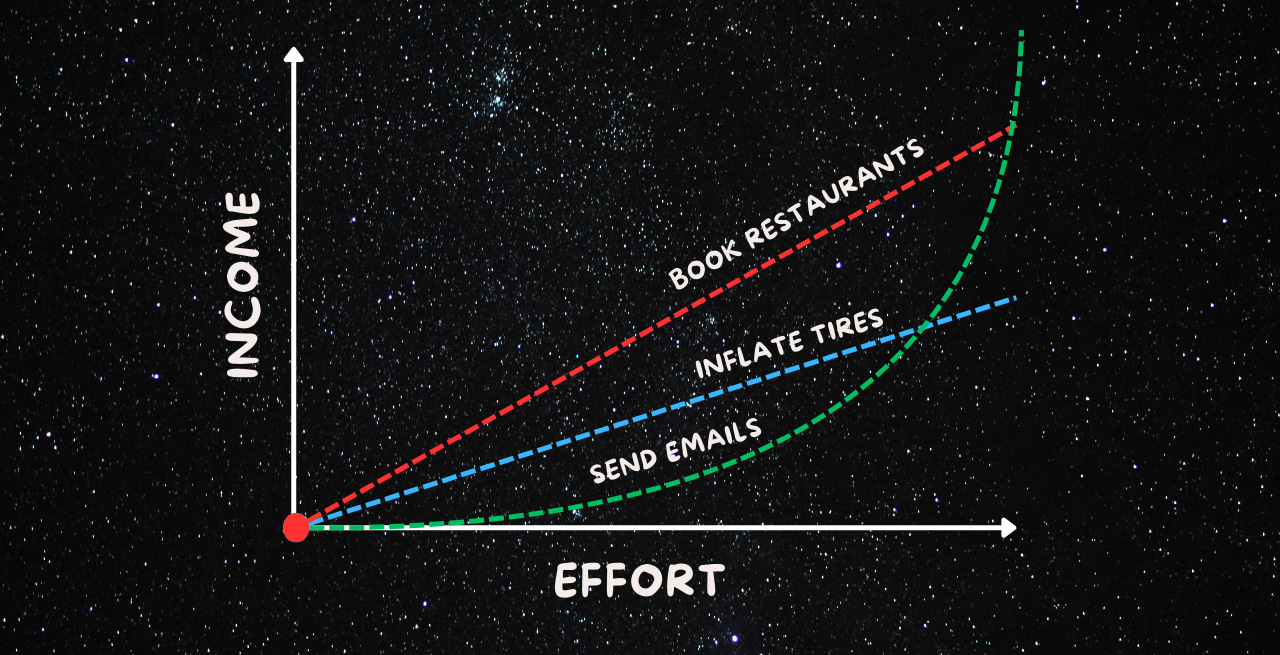

When you expand your vision, you begin to see resources and skills that were always there but invisible. The question everyone asked was, “How do I turn 5 into 10?” And that’s when their vision narrowed. That’s linear thinking: more work, more income—like those who inflated tires or booked restaurants.

The winning team didn’t rush. Instead, they started with:

“What are all the resources in this situation, and how can we use them?”

From this perspective, they saw the 3 minutes of presentation time. That was the most valuable resource. From Wednesday to Sunday, they organized everything. During the 2 hours after opening the envelope, all they had to do was send the same email to dozens of companies and wait for a reply.

Minimal effort, maximum benefit.

One generic email worked for all companies alike.

If you inflate tires, you can’t do that, you need to inflate each one individually.

If you book restaurant reservations, you can’t do that—you need to arrange each one.

Researching companies could be done from home, no 2-hour clock required.

Inflating tires required spending the $5 on a pump, then you only had 2 hours left.

Booking restaurants was like sending emails, but far more effort.

With emails, the only task within those 2 hours was waiting for replies and making a payment.

That is the power of non-linear thinking.

Effort and reward don’t move in parallel: the efficiency is disproportionate.

How to think non-linearly

Don’t rush to define the conditions

The first solution is usually simple, clear… and wrong.

In the challenge, the $5 was the mental trap. Instinctively, we think the $5 must be the resource—because money usually is—but that doesn’t mean it’s the only resource or the most valuable one. Use the option suppression technique.

Ask yourself: “What are all the resources? If there’s no money, what else is there?”

That’s when you start thinking outside the obvious.

Ask fundamental questions

Don’t jump straight to solving the problem, start by uncovering essential truths.

What’s the real problem? What’s your hypothesis, and why? What assumptions are you taking for granted? What evidence do you have? What options and alternatives exist? It’s a process of reflection: open questions, ideas, challenging ideas, iterating.

Before solving, set up the problem correctly.

That’s how the winning team reached their strategy. Once they identified that the 3 minutes of presentation could be a resource, they brainstormed ways to use it. These were their truths: “Companies will always want talent.” “Stanford students are valuable.” “Access to them is limited.”

When you follow the established path, your results will be incremental.

When you break free from linear thinking, your results can be exponential.

✍️ Your turn: If you looked at your situation from a different angle, what resources do you already have that you’re not yet fully leveraging?

💭 Quote of the day: “Wealth is the product of man’s capacity to think.”

— Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged

See you in the next letter, take care! 👋

Well, that was certainly a whup up the side of the head. Thanks you, Alvaro.