🏷️ Categories:

This story began in the fields of England in the 17th century.

Before, the land was open, a shared space where grazing and farming brought the rural community together, but then a problem arose. The population of the cities was growing fast and it was necessary to increase agricultural production to feed all those people.

It was necessary to change the model.

It was no longer enough to farm for self-consumption, it had to be commercial production.

The day finally came. The new landowners and aristocrats began to enclose their fields. From the 17th century onwards, English law made it compulsory to fence off fields to make them mechanised and private farms. ‘Efficiency’, some said. ‘Progress', insisted others. But at what cost?

There were many protests, as always.

They were crushed, as always.

The peasants could not buy property. They no longer had anything in the countryside, many left the land behind and went to the cities, seeking in the factories what the fence had taken away from them. Fences were a symbol of progress for some, migration and sadness for others (Hickel, 2018).

Fencing the countryside triggered huge changes that no one expected.

All those people had to migrate to the cities. As dramatic as it was, agricultural productivity increased and all that unemployed labour that ended up in the factories was what gave rise to the industrial revolution that changed the entire European continent in the following centuries (Overton, 1996).

It all started with fences in the field.

When should we maintain existing boundaries and when should we tear them down?

Can we aspire to create something new without destroying previous boundaries?

How much do we understand the impact of the choices we make?

When we take down and put up boundaries, it changes the boundary and everything around it.

Chesterton's fence

G.K. Chesterton, 20th century English writer and philosopher, has a lot to say here.

In his essay Heretics he posed an inspiring metaphor. If you find a fence in your way that blocks your path and you don't understand why it is there, don't remove it. Not yet. First, ask yourself why it is there. Only then can you decide whether to tear it down.

Before you change the world, know the purpose of things in the world.

The fence symbolises structures —laws, traditions, social norms— that seem obsolete or unnecessary at first, but which may have reasons we do not see that justify their existence.

Chesterton does not advocate immobility, he advocates reflection before change.

Removing and putting up fences without understanding why they are there has serious consequences.

The fence on the road to learning

This leads me to think about the way we learn.

Those other hurdles we accept when we start something new: rules, ideas, limits, conventions about ‘how to do things’.... At first, they seem absurd or annoying, they limit our creativity. But those fences are there for a reason. They guide you, they protect you from chaos, they allow the inexperienced person to move forward without getting lost.

Art students begin by copying the masters. They study the rules of colour, proportion and composition.

In writing we adopt established narrative structures and genres.

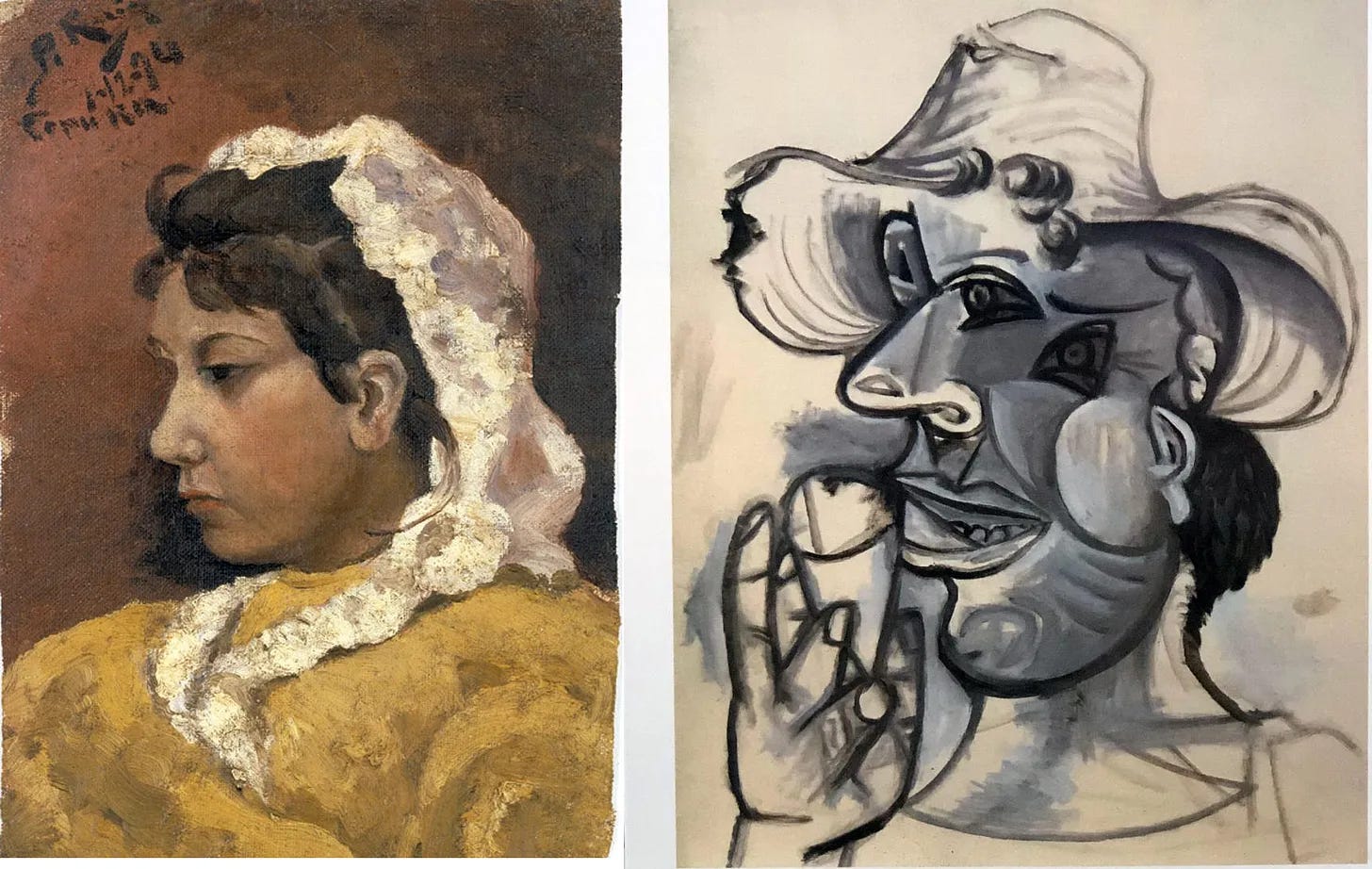

Picasso broke the rules of art because he understood them better than anyone else.

He is remembered for Cubism, but before that he mastered conventional styles.

Two Picasso paintings - do they look similar?

40 years difference between one painting and the other.

It's about destroying the established when you can push the limits further.

It happens in countless fields. Every rule learned is a small fence post that surrounds us. Only when you have walked inside that space and know every corner of it, you can break its boundaries.

That is Shuhari.

The social fence

I look outside. Not all fences are internal.

Some we inherited as a society: norms, hierarchies, traditions. They seem archaic, unnecessary. But are they always? While they may seem archaic, they serve critical functions, such as promoting order, cooperation and stability. It is easy to get rid of a tradition, but we do not always know what will happen next. Revolutions have been great exercises in tearing down.

In the French Revolution of 1789, entire structures were overthrown.

The vacuum they left was filled by Napoleon with a new order.

And so we are once again encircling what we had opened up.

The fence in changing habits

We all want to improve our lives in some way.

Sometimes we try to eliminate old and bad habits that we perpetuate, but we are not able to eliminate them because habits are like fences on the road: they are there for a purpose. The habit of smoking may have been acquired as a way to get rid of stress. A harmful way, but a way to do it.

If we eliminate that habit while ignoring its source, a new habit will fill that space.

Habits are behaviours that we have naturalised because they respond to a motive.

Again, to remove the fence, you have to know why it was put there. The easiest way to change a habit is to replace it with one that serves the same purpose, but in a more constructive way. Quitting smoking to do sport as a way of relieving stress.

Take down one fence to put up another.

Knowing how to break the limits

All this is nothing more than an invitation to humility.

The metaphor of the fence tells us that we are not smarter than the passage of time. That if through history we have accumulated knowledge and fixed certain fences, it is because they have a reason to exist. We may not see at first glance why the fence is there, but it encourages us to realise our own ignorance about the world.

We must understand the past before we want to change the future.

You can move forward and challenge the status quo, but first ask yourself a question.

Why does this limit exist?

✍️ It's your turn: Is there a fence in your way that you don't understand? I'm getting interested in fiction writing now. I don't know much and I keep coming up against hurdles that make me wonder, ‘Why do I have to do it this way?’ I want to innovate, but I still don't know much, it's better not to break down the boundaries.

💭 Quote of the day: ‘Whenever you want to tear down a fence, stop long enough to ask yourself why it was put there in the first place.’ G.K. Chesterton.

See you next time, respect the fences! 👋

References 📚

Chesterton, G. K. (2007). Heretics. Hendrickson Publishers.

Hickel, J. (2018). The divide: Global Inequality from Conquest to Free Markets. National Geographic Books.

Overton, M. (1996). Agricultural Revolution in England: The Transformation of the Agrarian Economy 1500-1850. Cambridge University Press.

UK Parliament. Enclosing the land. URL

As a writer on Substack, you are in one of the best places to be if you want to learn how to write. There are so many different kinds of work posted to Substack that will illustrate how writers and artists can learn about the fences as well as experiment with a story or poem you're working on. Go for broke and branch out with something new that you haven't tried before. You find out where the fences are and why as well as where the gates are too.

Excellent article, thank you.