How social pressure manipulates you

You prefer to fit in rather than be yourself

🏷️ Categories: History, Decision making and biases, Social relationships.

Sometimes, group pressure can make a lie become the new truth…

More than 2,000 years ago, the great Chinese historian Sima Qian recorded in his monumental work Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian, ca. 91 BCE) an anecdote that became a proverb still cited in China today: “Calling a deer a horse” (指鹿為馬).

A story that seems absurd, yet holds one of the most powerful warnings about manipulation and social pressure.

In China, it is used to describe someone who distorts the truth and tries to convince others to believe it.

And so begins an ancient story…

After the death of the First Emperor Qin, the young Qin Er Shi ascended to the throne.

Inexperienced and dependent, he left the affairs of state to a high-ranking official named Zhao Gao. This man had already gained the emperor’s trust, but there were suspicions that he was plotting a conspiracy to seize imperial power. Ambitious and distrustful, Zhao Gao wanted to test the other ministers to see who was truly loyal to him…

On September 27, 207 BCE, Zhao Gao brought a deer into the throne hall.

He addressed the emperor: “I bring a horse for Your Majesty.”

The emperor frowned. “That looks like a deer,” he murmured. But Zhao Gao insisted: “If Your Majesty does not believe me, let the ministers give their opinion.”

The hall fell silent. Everyone saw a deer. Everyone knew it was a deer.

But that wasn’t the real question. The question was: Would they dare to say so?

Many ministers replied, “It is a horse.”

Some, braver ones, said, “It is a deer.” Zhao Gao took note.

Those who told the truth were punished. Those who repeated the lie survived. The emperor, confused and increasingly dominated by his tutor, eventually accepted Zhao Gao’s version: “Then it must be a horse.”

And so the proverb was born: “Calling a deer a horse.”

A lasting warning about the dangers of group pressure.

The Power of Conformity

What happened in the Qin court is not unusual.

It is a perfect example of human behavior.

Two millennia later, in the 1950s, psychologist Solomon Asch asked the same question that must have crossed Emperor Qin Er Shi’s mind when he saw the deer:

“Why do people say the opposite of what they see with their own eyes?”

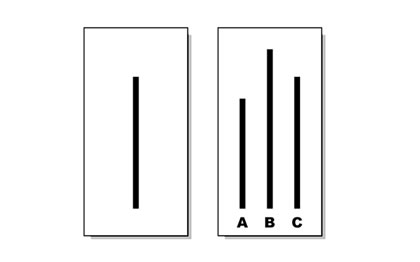

To demonstrate this, Asch designed a series of experiments. The most famous: the line experiment. All it required was a chalkboard, a reference line, and three comparison lines.

What Asch discovered confirmed what Sima Qian had documented 2,000 years earlier…

The Asch Conformity Experiments

In 1951, Asch gathered groups of eight college students.

Seven were actors, in on the experiment. Only one was a real participant. The task was simple: identify which of the three lines (A, B, or C) matched the reference line in length. The answer was obvious—impossible to miss. But here was the trick: in some rounds, the actors confidently gave the wrong answer.

The real participant always spoke last—just like the emperor.

After hearing seven people repeat an obvious mistake, would they say what they saw or what everyone else said?

The results were unsettling:

64.3% of responses were correct.

35.7% conformed to the group’s error.

74% of participants yielded at least once.

12% conformed almost every time.

Only 26% resisted in every instance.

Asch summarized it with a chilling line:

“That young, intelligent, and well-meaning people are willing to call white black is a matter of concern.”

What Lies Behind Conformity

After the experiment, Asch interviewed the participants. The findings were fascinating.

Those who resisted (the “independent” ones):

Acted with confidence: they saw the error, felt the pressure, but stood firm because they knew they were right and had evidence.

Some felt no pressure at all—they simply trusted their own perception.

Others doubted themselves but still held their ground.

Those who yielded (the “conformists”):

Perceptual distortion: a few truly began to believe their eyes were wrong and the majority was right.

Judgment distortion: many thought they misunderstood the task and that the group must be correct.

Action distortion: most admitted they knew the right answer but didn’t want to seem different or stand out.

Notice this: although 3 out of 4 people gave in, most did so for the same reason—

they knew the truth but didn’t want to say it for fear of being excluded.

The fear of rejection can lead us to defend the indefensible.

The Fear of Rejection

This pattern has a name in psychology: normative social influence.

Those who knowingly repeat a lie often do so not out of ignorance but fear—fear of being criticized, punished, or isolated. It’s the same as with the ministers of Qin: they called the deer a “horse” because telling the truth could cost them their position or their life.

And the situation hasn’t changed much in 2,000 years.

Today, the fear of rejection, ridicule, or losing status—on social media or at work—is as powerful as it was in Zhao Gao’s time. In our era, social pressure comes from millions of voices online and from algorithms that amplify what the majority says.

That’s why intelligent people repeat obvious lies.

That’s why societies and groups accept falsehoods as truth.

The power of the majority makes others change their stance.

It’s the law of social proof.

Zhao Gao and Asch’s experiments teach the same lesson: Group pressure can distort reality itself—until a deer becomes a horse.

But there has always been a minority who resisted.

In the Qin court, a few ministers told the truth despite the danger.

In Asch’s experiment, 26% stood firm, no matter what the group said.

The question that remains is personal…

When everyone says “horse,” and your eyes clearly see a “deer,” what will you say?

Social pressure can corrupt reality itself.

✍️ Your turn: Where do you see the “calling a deer a horse” phenomenon today?

💭 Quote of the day: “That young, intelligent, and well-meaning people are willing to call white black is a matter of concern.” — Solomon Asch

See you next time! 👋

📚 References:

Asch, S. (1951). Groups, Leadership and Men: Research in Human Relations.

Sima Qian. Records of the Grand Historian: Qin Dynasty.