Not everything needs to be optimized

Sometimes it's not a lack of effort, it's a lack of purpose

🏷️ Categories: Decision making and biases, Life lessons, History, Mental models.

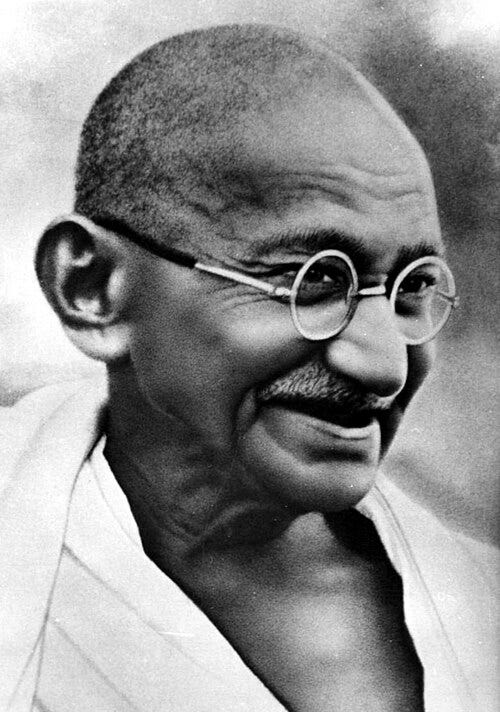

Mahatma Gandhi didn’t seem destined to change the world.

He was born in 1869 in India. He studied Law in London and began his professional career in South Africa. But his performance as a lawyer was, to be generous, unremarkable. He was shy, struggled with public speaking, and failed several times when trying to establish himself on his own.

For years, there were no clear signs of greatness.

He didn’t stand out for his oratory. He didn’t lead political parties. He didn’t hold important positions. If someone had evaluated his trajectory at that time, they would probably have concluded that he was an average professional, without any special impact.

And then something unexpected happened: he stopped trying to be a successful lawyer.

Instead of optimizing his legal career, he began to get involved in social causes. First, he defended the civil rights of the Indian community in South Africa. Later, he returned to India and joined the independence movement.

For decades, he devoted himself to nonviolent resistance.

A form of political action that seemed ineffective or naïve. Marches. Hunger strikes. Peaceful civil disobedience. None of that seemed like an effective strategy against the power of the British Empire.

But it changed everything.

His vision changed the course of Indian history and left a legacy for modern politics. He inspired civil rights movements around the world and redefined the concept of leadership. Today, he is remembered as one of the most influential figures of the 20th century.

And all of this came from something that seemed inefficient.

We’ll return to his story in a moment.

Efficiency vs. Effectiveness

You only have one life. How do you decide the best way to use your time?

Productivity experts would tell you to focus on being effective, not just efficient.

Efficiency is about doing more things with fewer resources.

Effectiveness is about doing the right things well.

Put another way: working on the right thing is more valuable than working hard and efficiently on anything else. Progress isn’t just about being productive. It’s about being productive in what truly matters.

But how do you decide which are those “right things that matter”?

One of the most commonly used ideas is the Pareto principle.

The 80/20 rule states that, in many areas, a minority of causes generates the majority of results. A small percentage of people own most of the land. A few teams win most championships. The exact figures don’t matter much. What matters is the relationship.

Applied to life, the 80/20 rule helps separate the vital from the trivial.

It’s a great strategy. I’ve used it myself many times and it works wonderfully, but this rule has a dark side that many people ignore…

To understand it, let’s go back to Gandhi.

The Dark Side of the 80/20 Rule

Imagine we’re at the beginning of the 20th century.

Gandhi is trying to decide how to use his time and energy.

If he applied the 80/20 rule to his career up to that point, the answer would be clear: focus on his career as a lawyer. That’s where his income, stability, and professional track record were. If the goal was to maximize measurable impact, the effective move would have been to become a more efficient lawyer, specialize, and progress within the existing system.

Even if his intention was to help his community, an 80/20 analysis might have suggested that earning more money as a lawyer and funding social causes would be better.

All of that makes sense… if Gandhi had wanted to keep being a lawyer.

But he didn’t.

He wanted to change a structural injustice, and to do that he needed to take to the streets and mobilize people. And there was no analysis suggesting that nonviolent resistance (led by a man with no political or military power) would be effective.

Here lies the central problem of the 80/20 rule: a new path almost never looks like the most effective option at the beginning.

Optimizing Your Past or Building Your Future?

Consider another example.

Reed Hastings, founder of Netflix, had built a successful business mailing DVDs. In the early 2000s, that model worked well: it grew steadily, had loyal customers, and generated increasing revenue.

If Hastings had used the 80/20 rule, he would have thought exactly what you’re imagining…

Optimize the DVD business.

That’s where it made sense; that’s where most of the revenue and accumulated experience were. Measured in profitability, stability, and common sense, improving what already existed was the most effective option.

But it wasn’t.

Betting on watching movies over the internet, on the other hand, seemed doubtful. The technology was still immature, the infrastructure very limited, and consumption habits hadn’t formed that way yet. It was a complete transformation of the business.

From any analysis based on past results, it didn’t seem optimal.

This happens because the 80/20 rule is always calculated based on your recent effectiveness. What seems to provide the greatest value for your time depends on the skills you already have and the opportunities that already exist.

The 80/20 rule helps you find what works and maximize it.

But if you don’t want your future to be a repetition of your past, change the focus.

The cost of being too effective is that you often end up optimizing what already worked, and you lock yourself into it so deeply that the sunk cost bias makes you undervalue the rest of the options. And that can end up being catastrophic.

Now let’s look at exactly that case…

The Kodak Case

For much of the 20th century, Kodak was synonymous with quality photography.

Its core business (selling photographic film and photo development) was extremely profitable. Most of its revenue and internal expertise came from that model. From an 80/20 perspective, the decision was obvious: further optimize analog photography.

That’s where the money was, the customers, the experience… They were the kings of the market.

Ironically, Kodak was one of the first companies to develop a digital camera… but the product didn’t seem promising, it was unexplored territory and, of course, less profitable. So Kodak did exactly what the 80/20 rule would have recommended: protect the business that worked.

Meanwhile, the world changed. And very fast.

Over time, digital photography became dominant, Kodak’s business collapsed, and the former market king ended up filing for bankruptcy in 2012.

Kodak didn’t fail due to inefficiency.

It failed because it was too effective at playing the wrong game.

What Should You Do Now?

Here’s the good news: with enough time and practice, what once seemed ineffective can become highly effective.

You become good at what you practice.

When Gandhi began with nonviolent resistance, it seemed useless against imperial power. Decades later, his approach achieved India’s independence and influenced civil rights movements around the world.

It’s unlikely he would have achieved that by trying to be a more efficient lawyer.

Learning a new skill, starting a business, or beginning a new life chapter almost always looks like a bad investment at first. We struggle to visualize the distant future; it’s easier to see the short term. That’s why these changes never seem right.

Compared to what you already know how to do, the new path looks like a waste of time.

The 80/20 analysis never wins when it’s time to change direction.

But that doesn’t mean your new direction is wrong.

Want to Learn More? Here Are 3 Related Ideas to Go Deeper:

Bonfire Effect: Being exhausted without having moved a single step forward

Want more luck? Use this mathematical trick from the Pareto Principle

✍️ Your turn: What decision would you make if you stopped asking “what works best right now” and started asking “who do I want to become?”

💭 Quote of the day: “It is our choices, Harry, that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities.” — J. K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.

Until next time, good luck! 👋

New to your posts, Love your newsletters👍always full of just enough research gems