Elmore Leonard’s 10 Rules for Mastering the Art of Writing

Notes on giants - Number 16

Welcome to Mental Garden. The following letter is part of our "Notes on giants" collection, in which we explore the thoughts of humanity's greatest minds.

To see the full library, click here.

🏷️ Categories: Writing.

There’s a kind of writer who wants to speak to the reader.

In every sentence, they shout at the reader through exclamations in dialogue.

In every sentence, they tell the reader what to feel through descriptions.

In every sentence, they explain how things happen using adverbs.

But there’s another kind of writer… Writers who let the story speak for them.

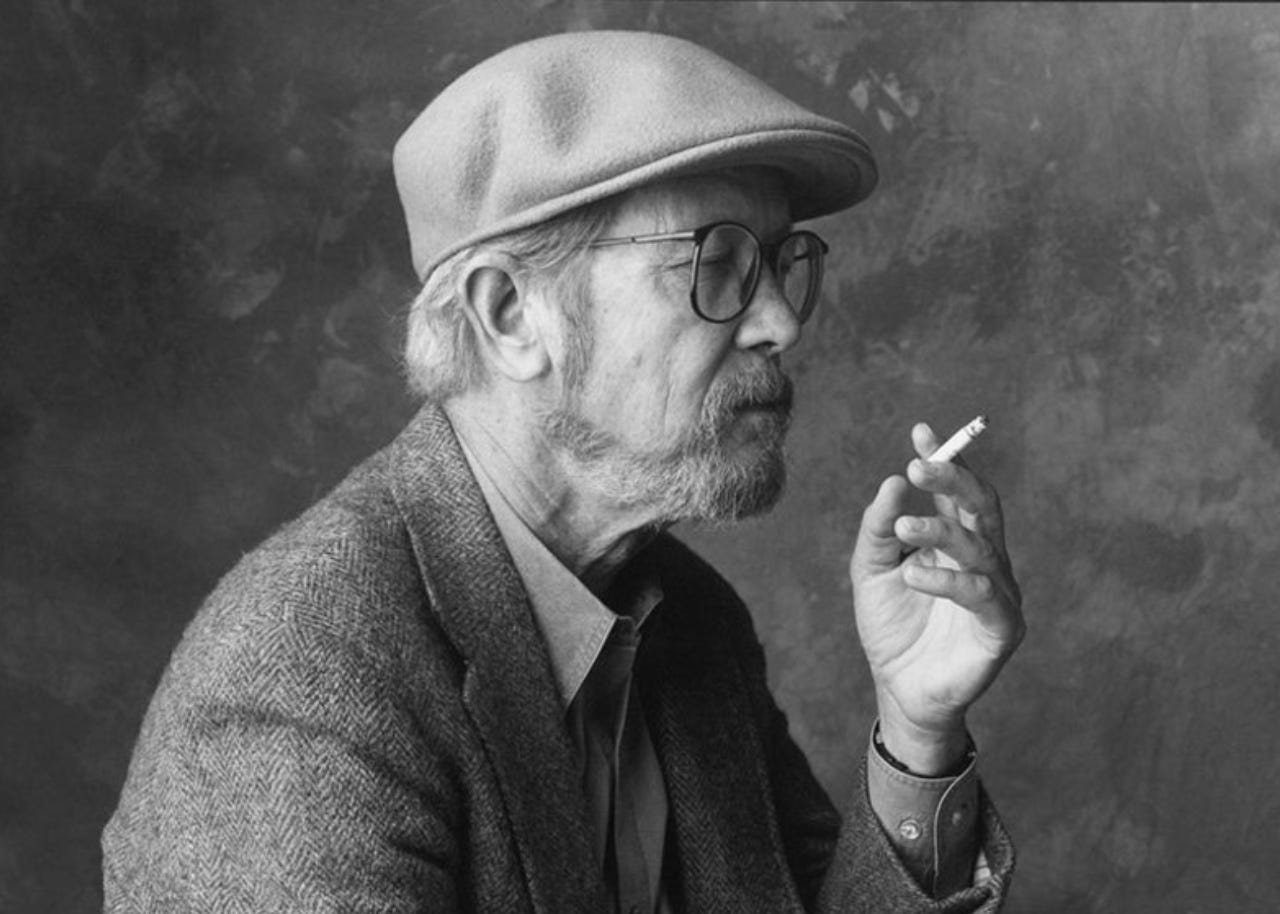

Elmore Leonard was one of them, and today I want to share his 10 essential rules for improving your writing. Elmore was one of the best American novelists of the 20th century and distilled all his experience into a single book.

The goal?

To take your writing to the next level—starting today. It doesn’t matter if you’re just beginning or if you’ve been writing for years. These ten lessons will save you years of trial and error, because what took Elmore decades to learn, you’ll find right here.

Let’s dive in.

1. Never start a book with the weather

“If it’s just to create atmosphere, and not a character’s reaction to the atmosphere, you don’t want to go on too long.” — Elmore Leonard

Elmore noticed this pattern in many beginner writers.

Starting with the setting is usually a mistake. It’s like inviting someone to your house and leaving them staring out the window instead of sitting down to talk to them. Writers often rush to describe the fascinating world they’ve built—but the reader wants the story, not the setting.

Introduce atmosphere only when it serves a narrative purpose.

If the reader doesn’t know why they’re reading about the landscape, the city where the story takes place, or the tech level of a civilization, they’ll probably skip ahead. But if the setting reflects the character’s emotional state or directly influences the action, then it matters—it adds value and keeps the reader engaged.

Example: Instead of “It was a gray, rainy day in the city…” try: “Marta hunched under the downpour as the third call came through. She couldn’t avoid it any longer—she had to talk…” Now the weather carries emotional weight. It’s brief. It enhances the scene.

2. Avoid prologues

“A prologue in a novel is backstory, and you can drop it in anywhere you want.” — Elmore Leonard

For Elmore, a prologue is like speaking before the movie begins.

It’s an attempt to justify what’s coming, when ideally the story should speak for itself. Just shut up and let the story happen. And if the context really matters, you can introduce it gradually in the first chapters. Don’t put roadblocks in front of the reader—prologues are often just an excuse to avoid starting with what truly matters.

The reader wants to enter the story, not the summary.

Example:

If your prologue explains a war that happened a hundred years ago, ask yourself: Can I show this through dialogue, flashbacks, or current events? Most of the time, yes.

If your alien invasion story starts with a kid on a farm—don’t open with that. Start with the imminent invasion and reveal, piece by piece, how a kid in a wheat field raised the alarm. No matter how epic your story is, it will sound slow and underwhelming if it opens with a kid on a farm.

3. Don’t use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue

“The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in.” — Elmore Leonard

“Said” is the most invisible verb you can use.

It doesn’t get noticed, it doesn’t interrupt, and it lets the character shine. Verbs like “shouted,” “grunted,” or “explained” are the author trying to steer the reader’s emotions. They tell you how the character feels instead of letting you experience it.

And that breaks the connection.

The reader stops listening to the character and starts noticing the writer. But Leonard wanted the opposite: to disappear from the page. To be invisible and let the reader live freely in the story.

Example: Change “I hate you,” he growled angrily to “I hate you,” he said.

If the character truly hates the other, the scene and the dialogue you crafted will make that clear. Trust your writing—work on the setting and character behavior, and you won’t need these verbs.

4. Never use an adverb to modify “said”

“Using an adverb this way (or almost any way) is a mortal sin.” — Elmore Leonard

It’s not that Leonard hated adverbs. He hated when writers used them as a crutch. When you write “he said sadly,” you’re admitting the line doesn’t sound sad on its own. It’s the same problem as with verbs: some writers overuse verbs, others overuse adverbs.

And when you do this, the rhythm weakens.

The reader feels like the author is explaining something instead of showing it.

Example: Instead of “I’m so sorry,” she said sadly, try: “I’m so sorry.” Then add a gesture: She looked down, eyes avoiding his. If you write these small details well, you won’t need to tell the reader anything.

5. Keep exclamation marks under control

“You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose.” — Elmore Leonard

Punctuation communicates tone. If every other line includes “!”, then none of them stand out. Overusing exclamation marks shows an anxiety to emphasize without earning it. Leonard believed that if you build a scene well, the reader will feel the urgency—no shouting required.

Once again, the key is minimal author interference.

Elegant prose is the kind that shows without pointing.

Example: Instead of “Run! They’re going to catch us!” you might write: “Run. They’re going to catch us.” Let the tension come from what’s at stake, from the world you built, from short, impactful lines. As Virginia Woolf said: “It’s all about rhythm.”

6. Avoid phrases like “suddenly” or “out of nowhere”

“I’ve noticed that the writers who use ‘suddenly’ tend to exercise less control over their use of exclamation points.” — Elmore Leonard

“Suddenly” is a trap.

It tells the reader: “Feel this now.” Instead of building up to a moment that naturally surprises. Leonard hated emotional shortcuts. His point is consistent across all his rules: if you want a scene to surprise, build the surprise—don’t label it.

Create the context. Then drop the line that changes everything.

Example: Instead of “Suddenly, the car exploded,” just write: “The car exploded.” The impact is the same—or even greater—because of the sentence’s sharpness and timing. As Virginia Woolf reminded us: rhythm is everything. You build the high-speed car chase… and when the reader least expects it—it explodes.

7. Use dialect, slang, and onomatopoeia sparingly

“Once you start using onomatopoeia and loading the page with quotes for slang, you won’t be able to stop.” — Elmore Leonard

The line between effective and excessive is razor-thin.

Mimicking how a character speaks—catchphrases, unique quirks—can add authenticity, but too much of it can make your writing exhausting. Same goes for sound effects: if overused, they become noise.

Elmore’s advice, once again, is: suggest, don’t declare.

Use rhythm, occasional keywords, and grammatical choices to evoke a voice—without turning your page into a phonetic puzzle.

Example: Instead of “The door went ‘clack!’” you might write: “The door clicked shut.” And if your character speaks in a distinctive way, give a subtle sample. Don’t overdo it on every line or the reader will get tired. I once read a novel by Isaac Asimov where he made exactly this mistake—it was easily the worst part of the book. Don’t fall into that trap.

8. Don’t overdescribe your characters

“What do the ‘American and the girl with him’ look like? ‘She took off her hat and put it on the table.’” — Elmore Leonard

Look at that Elmore example.

What do those characters look like? We don’t know. Because what matters isn’t eye color or height—it’s what they do, what they say, what they avoid. Physical traits come second, unless they directly affect how the story unfolds.

Descriptions, used in moderation.

Example: Instead of “Maria was tall, slim, with brown hair and green eyes,” you could write: “Maria walked in with purpose, her brown hair swaying to her quick pace. She passed by without a word, as if she owed no one anything.”

Feel the difference?

Be careful—long descriptions pause the story. Experienced writers know when to describe, and when to let action carry the moment.

9. Don’t overdescribe places or objects

“Even if you’re good at it, you don’t want descriptions that freeze the story or break the flow.” — Elmore Leonard

Same point, but applied to setting—and even more dangerous.

The temptation to describe everything is always there. But Leonard urged restraint. A place should emerge as the story progresses. You don’t stop the narrative to catalogue a room unless you have a reason.

You can detail a setting—only if it’s going to influence the plot or mood.

Example: Instead of “The living room had a red sofa, a standing lamp, two bookshelves packed with books, and a Persian rug,” try: “The room smelled of old books, and someone’s coat lay on the red sofa—clearly not planning to stay long.” That’s enough. The description now sets a tone, not a list.

10. Skip what readers tend to skip

“Think of what you skip while reading a novel: thick paragraphs of prose where you see too many words.” — Elmore Leonard

The final rule says it all: only write what the reader will want to read.

And yes, that usually means dialogue, action, tension—not endless introspection or poetic detours that go nowhere. Leonard called these “writer detours”—unnecessary tangents. His rule was simple: if a reader can skip it and enjoy the story just the same, you’re better off not writing it.

Example: If you’ve written three paragraphs about a character’s past, ask: Can I reveal this in a single line of dialogue? Or in a decision they make later? If yes—cut it.

And remember to tailor it to the genre. If you’re writing a fast-paced thriller, you can’t interrupt the flow with deep philosophical monologues about your character’s childhood.

What you take from these 10 rules is one thing: clarity.

If you paid attention, you’ll notice most beginner writers have one recurring problem: overinformation. Overdescribing characters, settings, overusing verbs (“said” vs. “growled”), or unnecessary adverbs… It’s a problem of quantity. Elegance, in writing, is saying more with less—not screaming meaning at the reader.

When you write, ask yourself:

Am I telling the story? Or am I letting the story speak for itself?

That’s the difference.

That’s where mastery begins.

Because writing well, in the end, is knowing what to leave out.

✍️ Your turn: What writing advice helped you most? Even though I write nonfiction, I share Elmore’s same philosophy. His vision reminds me of Asimov in the best way.

💭 Quote of the day: “If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.” —Elmore Leonard, 10 Rules of Writing

See you in the next letter! 👋

📚 References

Leonard, E. 10 Rules of Writing

What do you think of Joseph Conrad’s first paragraphs? For example in Heart of Darkness:

“A haze rested on the low shores that ran out to sea in vanishing flatness. The air was dark above Gravesend, and farther back still seemed condensed into a mournful gloom, brooding motionless over the biggest, and the greatest, town on earth.”

Good lessons all. In essence, rite tite.