Welcome to Mental Garden. The following letter is part of our "Notes on giants" collection, in which we explore the thoughts of humanity's greatest minds.

To see the full library, click here.

🏷️ Categories: Life lessons, Writing.

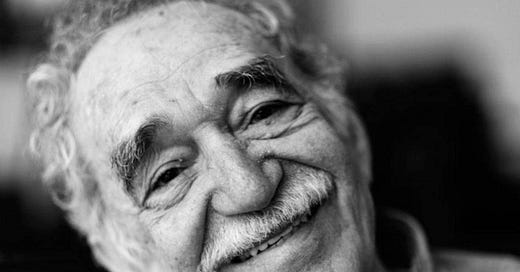

“The worst part was that at that stage of writing no one could help me, because the cracks weren’t in the text but inside me, and only I could have the eyes to see them and the heart to suffer them.”

— Gabriel García Márquez, Living to Tell the Tale

This is for you.

For the one who was told that writing is a bohemian luxury, not a serious job. You grew up hearing it was fine, but you should look for “something real.” A safe career.

Everyone was told the same.

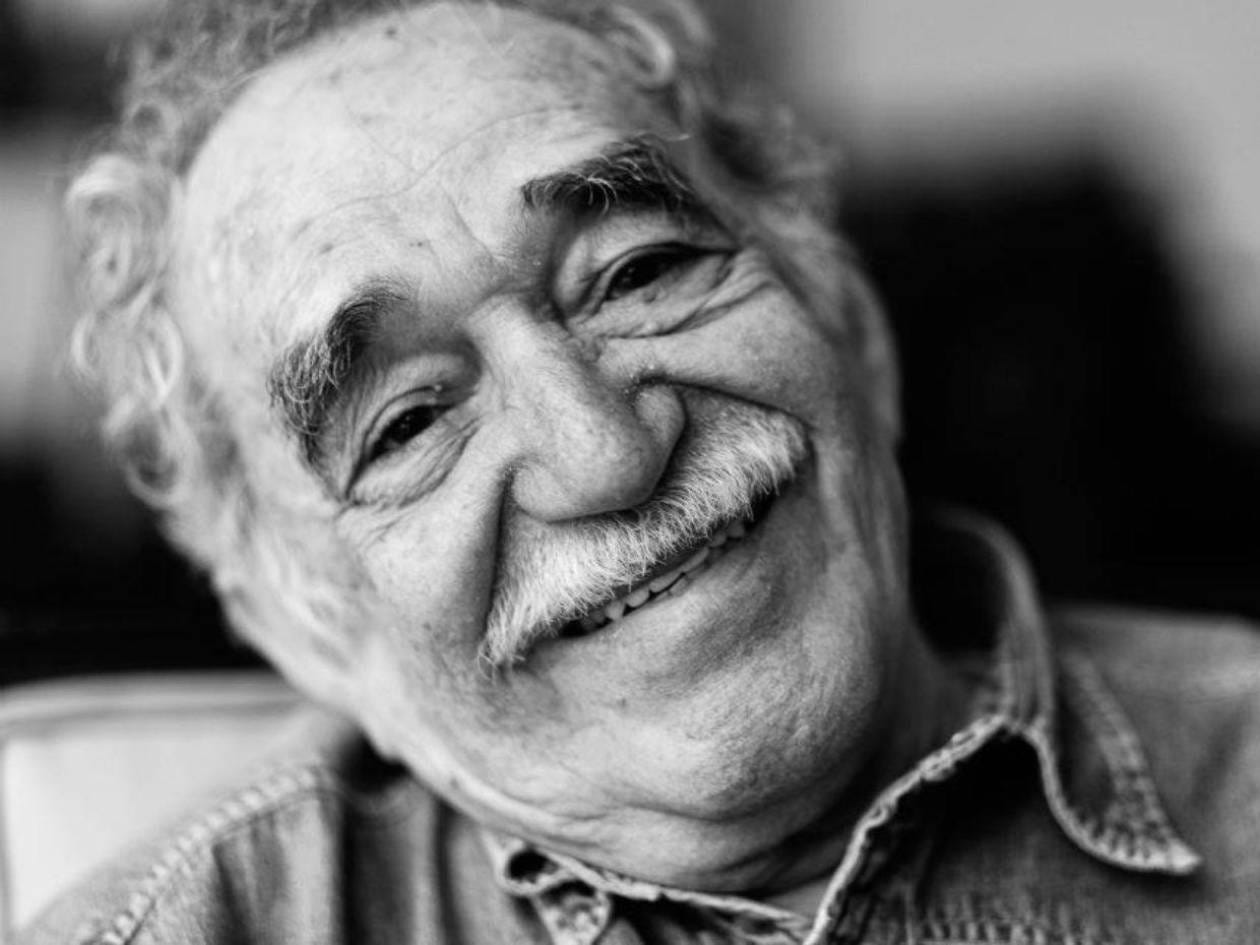

Even Gabriel García Márquez —yes, the Nobel Prize winner, author of One Hundred Years of Solitude, one of the greatest of all time— faced the same things…

Lack of money, family pressure, self-doubt, fear of failure, perfectionism… and that question that kept him up at night:

Is this really worth it?

Let’s take a look at his beginnings. Because no one starts at the top. Even giants were invisible once. If today it feels like writing is a losing battle, like your voice doesn’t matter, listen to me:

You are in the right place.

Gabriel chose to become a writer. Despite the fear.

We’re told the story of the innate genius as if there were no other way.

As if not shining from childhood means we’re already too late. But Gabriel García Márquez wasn’t a prodigy. He didn’t even consider becoming a writer…

He dreamed of singing and playing the accordion.

“Back in my days in Aracataca, I dreamed of the good life, going from fair to fair, singing with an accordion and a good voice — it always seemed to me the oldest and happiest way to tell a story.”

It was during his teenage years that he became passionate about literature, something his parents rejected from the start. His family had other plans. In his environment, being a writer wasn’t a profession—it was a youthful bohemian whim.

This is how Gabriel’s mother spoke to him when he was eighteen:

“—At least promise me you’ll finish high school as best you can, and I’ll take care of the rest with your father.

—I agreed, for her and for my father. That’s how we landed on the easy solution: that I would study law and political science…”

Gabriel was sent to Bogotá to study law only to meet family expectations. He never finished the degree. After many tears, arguments, and his mother’s desperate attempts to make him reconsider, he stood firm.

When she asked him why, he replied:

“—I don’t know what we’re going to do—she said after a deadly silence—because if we tell your father all this, it might kill him on the spot. Don’t you realize you’re the pride of the family?

—Then I’ll be nothing at all—I concluded—. I refuse to be made into something I don’t want to be.”

His answer was full of despair.

He was tired of living to meet expectations that didn’t reflect who he was. He wanted to follow his desire to be a writer, even if that meant a life without certainties. No income. No prestige. But it also meant choosing the freedom to be himself.

Eventually, she resigned and supported him in his “whim” despite everything.

“If you set your mind to it, you could be a good writer.”

To which Gabriel replied:

“If I’m going to be a writer, I’d better be one of the greats, I told my mother. After all, there are better jobs to starve to death in.”

That sentence says it all.

He wasn’t a confident young man. He wasn’t even sure of his calling. He had fears and doubts that he masked with irony. Like anyone who’s loved something fiercely, he was terrified of trying and failing. He was an ordinary person who loved words.

Like you. Like me.

An unstable life

In his early years, he lived between poverty and uncertainty.

He wrote daily press notes and columns, often unsigned. He was invisible. And despite his efforts, he himself considered his writing mediocre due to his harsh self-criticism. As he put it:

“I alternated my leisure time between Barranquilla and Cartagena de Indias, surviving on what I was paid for my daily notes in El Heraldo, which was almost less than nothing.”

Once, speaking about an article he wrote on Edgar Allan Poe, he said:

“Its only merit was being the worst…”

One day, a family acquaintance saw him on the street and was scandalized to see him working in what she saw as a beggar’s job. She scornfully said:

“What would they say if they saw the favorite grandson handing out flyers…”

It was her way of saying: you’ve failed, stop trying.

But he didn’t see it that way. To him, writing was how he understood life—a dream worth fighting for even when the world told him to give up.

He couldn’t find his voice

If you doubt your voice, that’s normal. Gabriel spent years trapped in other people’s styles.

He tried to write like the poets of the Spanish Golden Age, like the modernists, like Lorca. In his youth, he was a voracious reader who fell in love with every author’s style and tried to mimic them. In Vivir para contarla, he admits:

"I had begun with imitations of Quevedo, Lope de Vega and even García Lorca. I went so far in that fever of imitation that I had set myself the task of parodying every one of Garcilaso de la Vega's forty sonnets.

Everything I wrote were shameless imitations."

He tried poetry, short stories, essays. He constantly changed styles. He got tangled in formulas that didn’t satisfy him. Nothing sounded right—it all felt fake. But through stumbles and frustration, he slowly forged his voice.

One of his first steps toward finding his own style was this realization:

“Practice eventually convinced me that adverbs ending in -ly were an impoverishing vice. I forced myself to find richer, more expressive forms. It’s been a long time since one appeared in my books.”

This would force him to find richer expressions, more of his own. More your own.

Writing with style has to do with that, with making it sound like you. The craft of writing is no exception, like any craftsman, every writer has a toolbox to work with.

This is how style is forged by using adjectives, nouns and adverbs in a peculiar way.

He got stuck. A lot.

La hojarasca, his first novel, was a nightmare.

It took him years to finish. Many times he felt the book made no sense, that it went in circles, with characters and plots that led nowhere.

“After a year of work, the book revealed itself to me as a circular labyrinth with no entrance or exit.”

He felt it lacked coherence—just a pile of pages that didn’t fit together. His inexperience as a young author damaged his self-esteem.

“The worst part was that at that stage of writing no one could help me, because the cracks weren’t in the text but inside me, and only I could have the eyes to see them and the heart to suffer them.”

The insecurity was brutal. Every page was a battle, and when he finally published it, the book went unnoticed. It was ignored. But looking back, he knew La hojarasca was a necessary first step.

It was his first serious attempt.

“One ordinary day I was handed a letter in El Heraldo. La hojarasca had been rejected. I did not have to read it in full to feel that at that instant I was going to die. The only consolation was the surprising concession at the end: ‘The author must be recognized for his excellent gifts as an observer and a poet’.”

His first constructive failure.

“La hojarasca - rejected or not - was the book I had set out to write.”

As his friend Alfonso Fuenmayor told him after hearing the news:

“The only thing you have to do from now on is to keep writing.”

He was afraid to write

Gabriel García Márquez wasn’t born the great writer we know.

He was an insecure young man. And even in his maturity, he never got rid of the fear of writing. That fear didn’t vanish—it became part of the process. Every new book brought vertigo, doubt: What if this is the one I can’t finish? What if all the rest was just luck? It’s not the confession you expect from a genius, but there it is: the fear of writing.

“I’m a slave to a perfectionist rigor. I used to think it was responsibility, but now I know it was pure, physical terror.”

It doesn’t matter how many books you’ve written.

It doesn’t matter how many times you’ve done it.

That fear doesn’t go away. You learn to live with it.

And if today, you’re out there writing—even without a plan, even if you think you’re wasting your time… You’re not. You’re doing exactly what García Márquez did.

As he himself said:

“The terror of writing can be as unbearable as the terror of not writing.”

So write.

Out of fear.

Out of rage.

Out of love.

But write.

Because no one is born at the top.

✍️ Your turn: Have you ever gone through that phase where you doubt your own writing? I have. It always comes back, it never really leaves.

💭 Quote of the day: “I had no direction, neither that night nor in the rest of my life.” — Gabriel García Márquez, Living to Tell the Tale

See you in the next one — and keep writing until then! 👋

References 📚

Márquez, G. G. (2002). Vivir para contarla.

Powerful and inspiring! I always doubt my writing and editing over and over. Sometimes, I feel invisible, but I remember I am doing what my heart says. My heart says, “Write.” Thank you for sharing.

Thank you for this article on Marquez. I have One Hundred Years of Solitude sitting on my stack of BTBR. Now I can understand the man behind the book and will enjoy it much more.