🏷️ Categories: Mental models, Geography.

I remember perfectly the first time I heard that phrase.

It was in one of my university cartography classes, yes, because I studied geography.

‘The map is not the territory’, said my cartography professor with complete naturalness, stating something he saw as obvious. At the time, it sounded to me like one of those phrases that sounded so loud but were empty of meaning. I didn't know what he meant.

Don't we use maps all the time to understand the territory?

Aren't they reliable tools about the territory?

Don't they represent reality?

No, they don't.

What I didn't know was that this phrase would become one of the most powerful ideas I have ever known for understanding reality and making decisions. With time, one matures. I understood how common it is to confuse what you see with what happens?

To confuse the map with the territory.

And that confusion is the cause of many bad decisions.

If you have ever trusted information that was correct and ended up leading you down the wrong path, you will see why this paradox happens. You will see why the map is not the territory, no matter how much Google Maps and your GPS would have you believe otherwise.

Maps are imperfect by definition

All maps are wrong. Absolutely all of them.

The idea that ‘the map is not the territory’ comes from the philosopher Alfred Korzybski, who said that any representation of reality is always a simplification. Even the most detailed maps cannot capture the full complexity of a place. It is impossible for a map to be the complete reality.

Everything is a simplification.

If a map tried to represent every tree, every rock and every stream in the terrain, it would be so gigantic and so difficult to understand that it would be useless. For a map to be practical, it must reduce the information to the essentials, and that comes at a price.

That reduction involves omissions, interpretations and, in some cases, distortions.

It is not only a question of detail, it is also a question of time. A map from 10 years ago might be useless today if the roads have changed. The same is true for the mental models we use to make decisions.

What worked in the past may not be valid in the present.

It was not on my map

We all use maps to navigate life. Models, graphs, reports, manuals, everything tries to represent reality (more or less).

For example:

A company's financial report: It is a representation of an organisation's economic situation, it may be doing well or poorly, but they tell us nothing about employee morale, product quality or the company's problems or good decisions. There is no context.

A resume: It can tell us a lot about a person's education and experience, but not about their actual ability to perform a job. People are often hired by looking at the map, not the reality.

Instruction manuals: They give guidelines on how to carry out a process, but cannot anticipate the particularities of each user and problem.

When we blindly rely on these maps without touching the territory, we fall into the trap of making decisions based on incomplete or erroneous data.

Jeff Bezos understood this perfectly.

In an Amazon meeting, someone assured him that the average wait time for customer service calls was 60 seconds. According to the ‘map’ (the data), everything was fine. But Bezos decided to check for himself and called customer service.

He waited more than 10 minutes (Lex Fridman, 2023).

The map was wrong.

Look at this: if the map and the territory don't fit, the problem is in the map. The way the data on wait times was collected was wrong. Jeff Bezos touched the territory and discovered the reality that the data was hiding.

You see the danger of relying only on maps without empirically testing the reality.

Don't forget what they are: representations of reality.

Seeing beyond the map

If no map is correct, how do we avoid making mistakes based on them?

1. Find the most up-to-date map

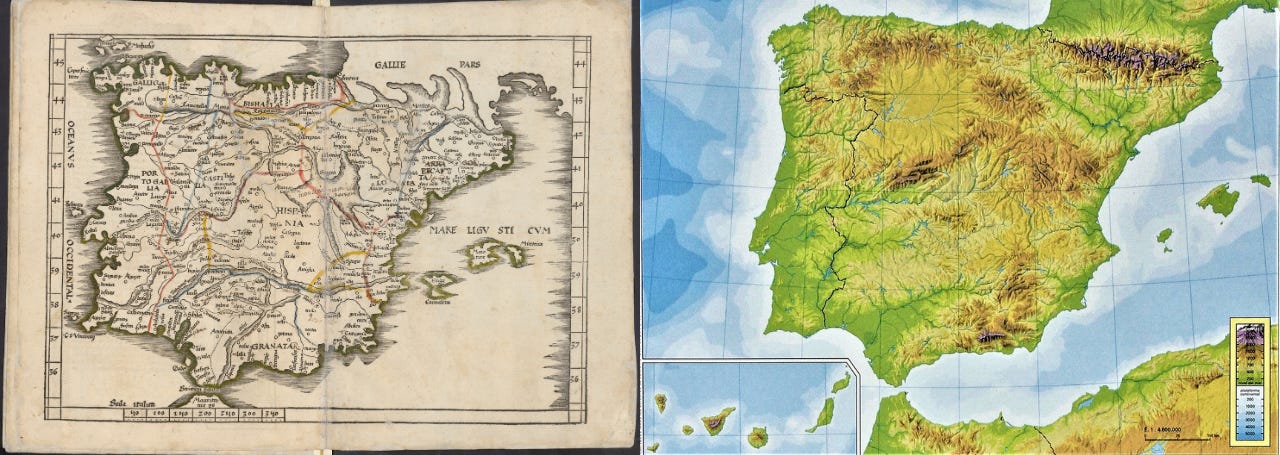

This is a map of Spain from the 16th century and this is a map of Spain from the 21st century.

Which one would you use to travel around Spain today?

The answer seems obvious, but it is not so obvious when you change the example.

Nobody would travel with a map from the 16th century, but there are those who make decisions based on erroneous data without noticing it. We tend to accept information without questioning it, without looking for better sources, so we are not as demanding as we are with a 16th century map.

No map is perfect, of course, but there are different degrees of error.

Raise your standard of information quality.

2. Touch the territory

If you can, leave the data and get down to reality.

Are you hiring someone? Don't just review their CV, put that person to the test in a real job case to assess their performance.

Are you going to register for a course? Don't just look at their website, visit the place, attend an open class, listen to people who are already taking the training.

3. Who made the map?

No map is neutral, be clear about that.

Every representation of reality has a creator with its own bias. Ask yourself: what information could have been distorted or simplified? What did the creator want to focus on with his map? Sometimes you will be in for some real surprises...

I recently received a proposal for a project that sounded very good.

Maybe too good.

On paper, everything was ideal: graphics, projections, investment, maintenance? The problem: their report detailed the pros well, but said almost nothing about the cons. When I did my own maths, I saw that the document (the map) was not objective.

The bias was more than obvious...

The data is neutral, the interpretation you make (or they want you to make) is not.

Use the data intelligently and you won't get lost.

The map is not the territory.

✍️ Your turn: What ‘maps’ have led you astray? I used to read everything about psychology, but being a young science, many theories have changed and the data was outdated. That's when I understood the value of choosing good maps....

💭 Quote of the day: ‘The map had been the first form of misdirection, for what was a map if not a way of emphasising some things and making others invisible? - Jeff VanderMeer, Annihilation.

See you next time! 👋

References 📚

Korzybski, A. (1934). Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics. JAMA, 103(3), 211.

Lex Fridman. (2023, 14 diciembre). Jeff Bezos: Amazon and Blue Origin | Lex Fridman Podcast #405 [Vídeo]. YouTube.

Great article. I've never thought of it this way. I do like to use paper maps, but especially when wandering in a wilderness, the roads can get a little wonky. Actually, urban areas have their pitfalls too with road construction, unnoted signage about one-ways, etc. Whew! I'll be sharing this with my husband who want to consult the economists at his workplace to find out what apps he can build that would help them do their jobs. He's speculating right now, but checking the terrain will certainly straighten out any misconceptions he has now.

Great post. There is a delightful video from Vox, the news site, that explains the different map projections. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kIID5FDi2JQ

One particular note is that simplification is almost always purposeful, that it makes it easier to do something—one could say the same of certain scientific ideas/models, such as Newtonian physics. We find it incompatible with Einstein and Quantum, and misconstrues the nature of mass, matter, speed, and time --- but it's super useful for certain things at certain speeds.

To make a broader point, James C Scott's masterful Seeing Like a State (a must-read) argued that nations more or less do this with all kinds of phenomena -- creating simplified abstraction from complexity. Sometimes, the consequences are disastrous.