🏷️ Categories: Decision making and biases, Learning, Zettelkasten

This letter is about thinking about whether what we think is really ours.

Yours, mine, are they really our ideas and opinions?

It seems an absurd question, but I wouldn't be so sure.

Opinion is often formed on headlines, on summaries, on listening, on what others have told you... (Ausat, 2023). (Ausat, 2023). It takes a great deal of effort to collate the amount of information needed to form one's own opinion. It is very tempting to stay on the shore of the sea of opinions, waiting for someone else's to wash up on the sand and make it our own. It is easier than venturing out to sea in search of truth.

Michel de Montaigne already said it centuries ago: ‘What is the use of having a belly full of meat if it does not digest, nor nourish us?’

That is what happens when you consume information without reflection.

The mind is full, but uncultivated.

The origin of opinions

Many of the opinions we hold are an accumulation of circumstances.

They are formed from an amalgam of personal experiences, information we acquire and information we receive from the influence of our social environment. From an early age, we are inculcated with the beliefs and opinions of our parents, teachers and friends, which shape our perception of the world. This socialisation process is based on imitation, so we replicate the views of those around us.

The truth is, if we had to debate with someone, we would not be able to defend many of our beliefs.

Even the most deeply held ones.

Intellectual laziness

The struggle to overcome intellectual laziness and form one's own opinions is not new.

Laziness is actually innate to human nature (Kahneman, 2011).

In 5th century BC Athens, Socrates was already grappling with this very problem, in a society that, despite its openness to debate, was seduced by the enchanted words of the sophists. They offered elaborate speeches that were in reality empty of argument, but which many people accepted without question. Socrates, with a questioning attitude, urged the people of Athens to reflect, but many were uncomfortable with his questions, for reflection requires effort.

More than 2000 years have passed.

Laziness is still the great enemy.

Today, it manifests itself in many ways, but perhaps the one that strikes me most is that of social networks. If dialogue is the path to truth, as the philosophers of old maintained, we could think that this space, where a torrent of opinions is produced, would be a hotbed of enrichment and knowledge. It would be something like the agora, but in a massified version. More people, more diversity of thought, more debate. Ideal, isn't it?

It is just the opposite.

In reality, social networks tend to lower the level of debate (Sunstein, 2018). They become a coliseum where positions are polarised and no one is willing to give in, but rather to impose their point of view and ‘defeat’ the other person publicly. Everyone sticks to his or her own truth, no matter what arguments you present.

And this is where algorithms come into play.

It is no longer just about us; it is algorithms that also design our consumption of content, shaping our opinions (Bandura, 1977). Every time you swipe your finger across the screen and interact, you hand over data to the algorithm, which, like a tailor, tailors a wardrobe of content that perfectly matches your beliefs. You feel so good in your position that you don't even consider that you might be wrong. Every time you log on to your social networks, you only see what reaffirms your position.

It's as if the whole world agrees with you.

Algorithms feed confirmation bias and remind us a bit of the fable of the naked emperor, where no one dares to tell the king that he is naked. In this case, the message is clear: we are never told that we might be wrong. If someone contradicts our opinion, the easy response is to ignore them; after all, 99% agree with you, so it is easier to think that this person, who feels alone in their disagreement, is wrong. This is a full-blown ad populum fallacy.

I find it funny the way they call those sections of content that the algorithm offers us to eat: ‘For you’, ‘Recommended’, ‘You might be interested in’...

I don't want it to be ‘for me’, because if it's ‘for me’, I know what's there.

Prefabricated opinions, perfectly aligned with my vision of the world.

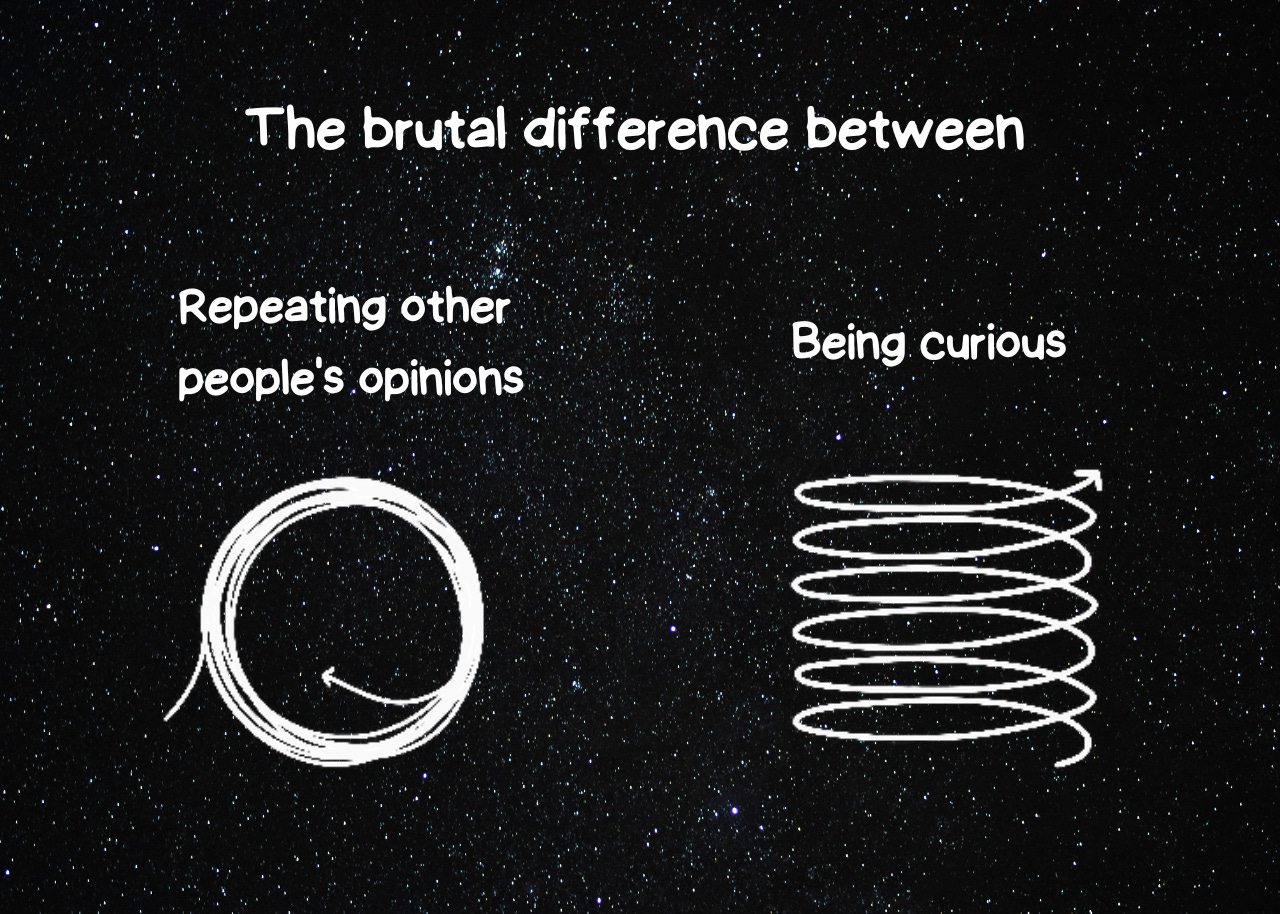

To enter this space is to fall into a vicious circle: the more you consume, the more you repeat other people's ideas and reinforce your beliefs without stopping to think of a single argument to defend them.

As Socrates rightly said: ‘A life that is not examined is not worth living’.

It is not easy, and it never will be.

In a world addicted to speed, stopping to think is an act of courage.

How to digest ideas properly

Taking up Michel de Montaigne's quote, how can we make sure that all the information that comes to us is well digested and nourishes us?

This is how I do it.

Whenever I become interested in a new topic or read a book, I make literature notes in my Zettelkasten. As I go deeper and take more notes, I begin to see discrepancies, nuances and connections between my ideas and those of other authors. It is in this process that the debate arises that enriches me, where I begin to connect the dots and form my own opinion. When I feel ready, with the facts on the table, I write a permanent note where I build my formed opinion.

These notes are what nourish me and give meaning to my vision of the world.

I don't know everything, nor will everything I think be true; but I make a deliberate consumption in which the priority is not to know more, but to know better. My opinions are just my tools to keep walking in the world. They are not perfect tools, but at least they are mine, not those I have borrowed and I don't even know why I carry them.

He who forges his tools is free; he who does not, lives at the mercy of what is lent to him.

✍️ It's your turn: What do you do to verify information and give your opinion?

💭 Quote of the day: «Only the educated people are free» Epictetus, Enquiridion.

See you soon, take care and reflect! 👋

References 📚

Ausat, A. M. A. (2023). The Role of Social Media in Shaping Public Opinion and Its Influence on Economic Decisions. Technology And Society Perspectives (TACIT), 1(1), 35-44. https://doi.org/10.61100/tacit.v1i1.37

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, N.J. : Prentice Hall ; Toronto : Prentice-Hall of Canada. [Enlace]

Epictetus. (2020). The enchiridion.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Penguin UK.

Plato. Apology

Samuels, M. G. (2012). Review: The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding from You by Eli Pariser. InterActions UCLA Journal Of Education And Information Studies, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.5070/d482011835 [Enlace]

Sunstein, C. R. (2018). #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media. Princeton University Press. [Enlace]

Will, F. (2023). Montaigne’s essays: Tackling It. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Whew! it is a constant struggle to take in the reams of information even from a select few sources. Trust is a huge concern as there is so much that is biased. And even for a 75-year-old lady sitting in her barcalounger in the afternoon, it's a struggle to stop and digest what has been generously bestowed. Even my current reading, "Maps: College and Last Poems" by Wistawa Szymborska, is proving to be a feast that is to be eaten and chewed one at a time. It is said that it takes about fifteen minutes of concentrating on an idea to take it from short-term memory to long-term. Oy! There is so much wonderful stuff that falls by the wayside of ideas, poetry, stories, etc. I'll died of exhaustion. Your method of writing notes for your Zittelkasten is a good idea.

Thank you for this post. It is absolutely true. I would add this. My therapist used to teach me which thoughts are mine and which are my parents' and even which thoughts originate in my anxiety. I know that opinions are more complicated than simple thoughts but the same process can be applied. I was surprised at first to learn that I can CHOOSE which opinions to label as mine. It was a funny process to dissect my mind and ask, "do I really think this?"