Tiny but powerful habits to sleep better and be more productive

Evidence-based tips to perform and rest better

"The best bridge between despair and hope is a good night's sleep.”

Matthew Walker, Why We Sleep.

Tell me how you sleep and I'll tell you how you'll do.

One third of your life will be spent sleeping. If you lived 80 years you would have slept more than 230,000 hours. Shocking to see sleep in figures, isn't it? In reality it doesn't seem so long to us because we are unconscious, maybe that's why many people don't give it the importance it deserves.

We focus on having a good diet, doing sports every day, studying better... basic habits for a healthy life, but do you know what they all have in common? We all do them while awake and they all depend on a single factor:

Sleep, that third of life that you spend without realizing it.

Worry about improving that third and the other two will improve on their own.

More sleep means more studying

The last review is not done while awake, it is done while sleeping.

It seems that sleeping is a moment of inactivity, but in reality the brain never stops working. While you sleep, new neuronal connections are formed in your brain and new dendritic spines, the key to the matter.

Dendritic spines are parts of neurons that store information and transmit electrical signals (Rochefort & Konnerth, 2012). What's so important about them? Well, during sleep, our brain processes the information gathered during the day and dendritic spines help to consolidate the information by creating new connections. In an interesting experiment with mice, it was found that, with the same hours of learning, mice that did not sleep afterwards formed fewer spines (Yang et al., 2014).

In other words, don't stay up late before an exam, organize yourself to study before and get a good night's sleep. I remember the days of exams, everyone would arrive with red eyes and eye-lashes saying that they had only slept a few hours. "This is what you get for leaving it to the last day," I would tell them.

Only when your rest is exceptional will your performance be exceptional.

When in doubt, sleep on it.

When I have a blockage and it's getting late, it's clear to me: I go to sleep.

Have you ever been stuck on something and just by going to sleep and coming back the next morning everything flowed effortlessly? This is very normal and I will tell you why:

What you see here are the sleep cycles. There are REM and four NREM (non-REM) phases. At night the brain goes through the different phases in 90-minute cycles, but if you look closely, at first there is more NREM phase and then more REM. And why is this important?

Remember the dendritic spines? Well, they develop the most during the first hours of sleep. In the NREM phase, memory is consolidated (Walker, 2009).

Then, the REM phase helps the brain to relate new information to old information (Stickgold et al., 1999), to solve abstract problems better, to find creative solutions (Walker et al., 2002) and also makes us able to solve numerical exercises we were stuck on faster (Wagner et al., 2004). Powerful, isn't it?

This has happened to me when I write. I start writing in the evening and can't get the words out; frustrated, I go to sleep. The next morning I come back and in 30 minutes I write in 30 minutes what I couldn't the previous evening in 1 hour. The difference? 8 hours of sleep.

What to do if you study at night

Some people claim to study better at night.

Most likely they are simply more efficient at that time because they are continuously distracted during the day and at night they have less stimuli, therefore they make better use of their time. Distractions are much more detrimental to performance than you imagine, in this article I explain it in depth.

If you are one of these people, this is the ideal order to sleep better:

Do the exercises or summaries first, everything that requires mental effort.

Review what you have practiced: Read the previous, avoid seeing new content, so you reduce the stimulation and consolidate your memory better.

In any case, whenever you can, study at other times because at the end of the day is when we are most tired and if the study session is longer than it should be you will be subtracting your sleep hours (Martin, 2020).

In the afternoon you would never have that problem.

The problem of screens and sleep

Light and coffee are very similar.

Light is the main stimulus that regulates vital rhythms, neurological and endocrine responses (Wehr, 1991; Klein et al., 1991). Moreover, there are light therapies for certain sleep disorders (Wetterberg, 2014). Imagine its importance.

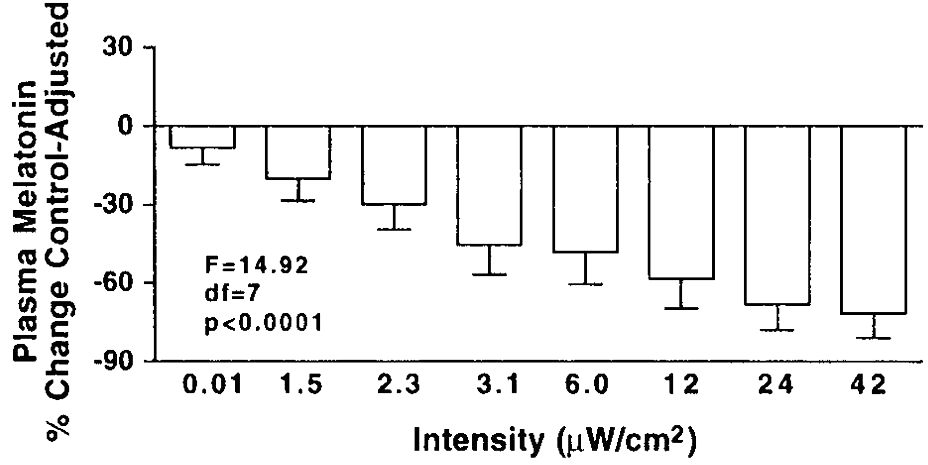

Electronic devices emit blue light, a type of shortwave light that has been shown to greatly reduce melatonin production (Brainard et al., 2001). Melatonin is the hormone that we secrete in dark environments and makes us sleepy. Most impressively, after comparing caffeine with blue light it was found that they produced similar effects: sleep inhibition and alertness (Beaven & Ekström, 2013).

During the night, with only 30 minutes of blue light, body temperature remains higher than usual, heart rate higher and melatonin production was reduced (Cajochen et al., 2005).

Look at this image from Brainard et al., (2001), they saw that the higher the intensity of blue light, the less melatonin was produced. Avoid using screens at night, with only 30 minutes of use you have already sabotaged your own rest.

— Hey, do you drink coffee to wake you up?

— No, I look at my cell phone.

See you soon... 😴

📚 References

Beaven, C. M., & Ekström, J. (2013). A Comparison of Blue Light and Caffeine Effects on Cognitive Function and Alertness in Humans. PloS One, 8(10), e76707. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076707

Brainard, G. C., Hanifin, J. P., Greeson, J. M., Byrne, B., Glickman, G., Gerner, E., & Rollag, M. D. (2001). Action Spectrum for Melatonin Regulation in Humans: Evidence for a Novel Circadian Photoreceptor. The Journal Of Neuroscience/The Journal Of Neuroscience, 21(16), 6405-6412. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.21-16-06405.2001

Cajochen, C., Münch, M., Kobialka, S., Kräuchi, K., Steiner, R., Oelhafen, P., Orgül, S., & Wirz-Justice, A. (2005). High Sensitivity of Human Melatonin, Alertness, Thermoregulation, and Heart Rate to Short Wavelength Light. The Journal Of Clinical Endocrinology And Metabolism/Journal Of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 90(3), 1311-1316. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-0957

Klein, D. C., Moore, R. Y., & Reppert, S. M. (1990). The suprachiasmatic nucleus: the mind’s clock. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263734011_The_Suprachiasmatic_Nucleus_The_Mind's_Clock

Rochefort, N. L., & Konnerth, A. (2012). Dendritic spines: from structure to in vivo function. EMBO Reports, 13(8), 699-708. https://doi.org/10.1038/embor.2012.102

Martin, H.R. (2020). ¿Cómo aprendemos? Una aproximación científica al aprendizaje y la enseñanza.

Walker, M. (2017). Why we sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams. Simon and Schuster.

Stickgold, R., Scott, L., Rittenhouse, C., & Hobson, J. A. (1999). Sleep-Induced Changes in Associative Memory. Journal Of Cognitive Neuroscience, 11(2), 182-193. https://doi.org/10.1162/089892999563319

Wagner, U., Gais, S., Haider, H., Verleger, R., & Born, J. (2004). Sleep inspires insight. Nature, 427(6972), 352-355. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02223

Walker, M. P., Liston, C., Hobson, J., & Stickgold, R. (2002). Cognitive flexibility across the sleep–wake cycle: REM-sleep enhancement of anagram problem solving. Cognitive Brain Research, 14(3), 317-324. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0926-6410(02)00134-9

Walker, M. P., & Stickgold, R. (2004). Sleep-Dependent Learning and Memory Consolidation. Neuron, 44(1), 121-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.031

Walker M. P. (2009). The role of slow wave sleep in memory processing. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 5(2 Suppl), S20–S26.

Wehr, T. A. (1991). The Durations of Human Melatonin Secretion and Sleep Respond to Changes in Daylength (Photoperiod). The Journal Of Clinical Endocrinology And Metabolism/Journal Of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 73(6), 1276-1280. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-73-6-1276

Wetterberg, L. (2014). Light and Biological Rhythms in Man. Elsevier.

Yang, G., Lai, C. S. W., Cichon, J., Ma, L., Li, W., & Gan, W. (2014). Sleep promotes branch-specific formation of dendritic spines after learning. Science, 344(6188), 1173-1178. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1249098