🏷️ Categories: Continuous improvement

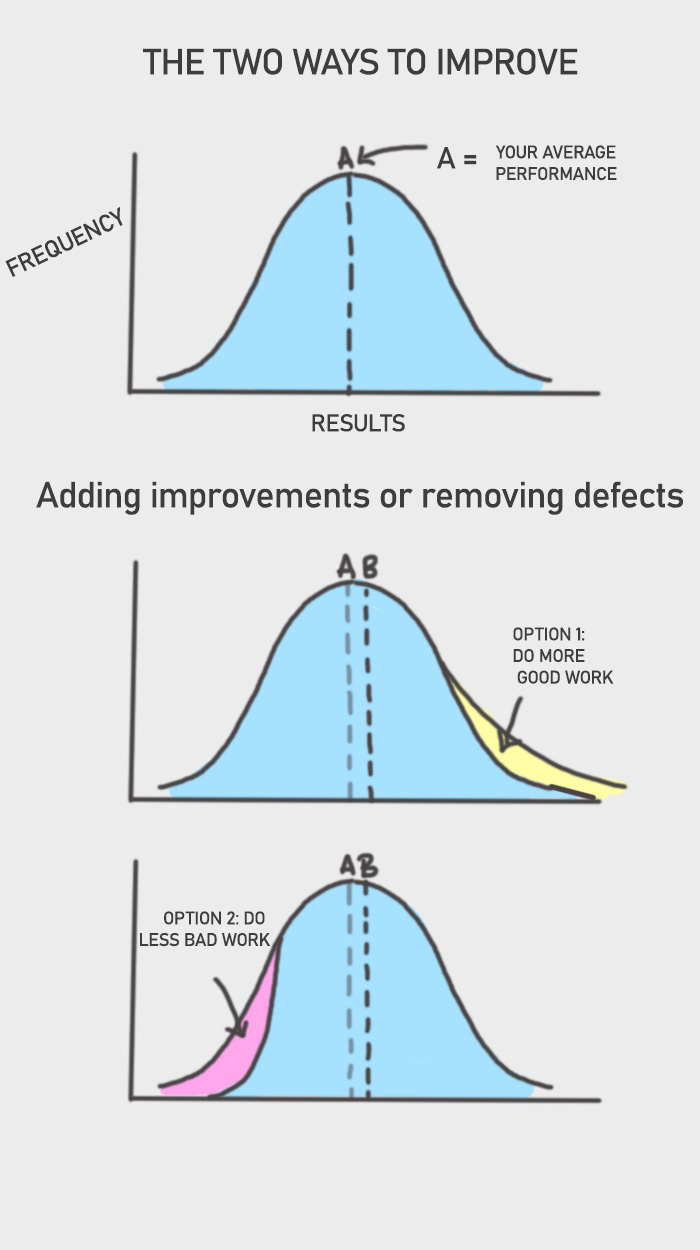

There are two paths to improvement: doing more things right or doing fewer things wrong.

This seemingly simple idea was one of the surprising innovations that boosted the productivity of Japanese companies and led the country to achieve the Japanese economic miracle of the 20th century.

It's amazing how something so simple has changed the way I see my progress.

Let's travel to Japan and discover the concept of “muda” (無駄).

After World War II, American industry was thriving, uncompetitive, and increasingly profitable, but the quality of its products barely improved over the years. Its dominance would evaporate in an instant when Japanese companies entered the market in the 1970s and swept the market.

Productivity in Japan between 1970 and 1984 grew three times faster than in the US (Fuss and Waverman, 1991), and by 1984, the Japanese were already 18% more efficient than Americans (Fuss and Waverman 1990).

For example, in the manufacture of televisions, in 1974, service calls for color televisions in the US were five times higher than those in Japan, and in 1979, American workers took three times longer to assemble their sets (Princeton University, 1990).

They were more productive, made fewer mistakes, and progressed faster.

Look at that, their great advance came from making fewer mistakes. They didn't have much more skilled workers or better infrastructure than the US, nor did they make larger or higher resolution televisions, they simply made the same product, but more reliable, longer lasting, in less time, and cheaper.

The Japanese asked the question the other way around, "How can I make the same television but with fewer errors?"

I wanted to see the potential of this idea had on a personal level so tested it.

Add improvements or remove defects

Everyone puts an excessive amount of effort into improving what already works and very little into fixing what is wrong.

We need to understand the following: the more we progress in some aspect, the greater the effort required to progress and the less progress is achieved. This is explained by the Pareto’s Law. We focus so much on continuing to add improvements that we forget that it would be simpler and have a greater impact to eliminate losses.

This applies to many areas of our life:

Study:

Improve: Study more hours.

Eliminate: Eliminate distractions and look for more effective study methods.

Finance:

Improve: Look for new sources of income.

Eliminate: Reduce unnecessary expenses and plan purchases.

Writing:

Improve: Write more pages a day.

Eliminate: Train creativity to have fewer blocks.

Training:

Improve: Do more repetitions or do them with more weight.

Eliminate: Avoid errors in your technique and avoid unhealthy food.

Both paths lead to progress, but the mindset is radically different. When adding improvements you focus on how to be better; when eliminating defects you focus on not getting worse.

Many small losses are a big loss

“Muda” (無駄, in Japanese), means “waste or squandering”, and you have already seen the philosophy behind it. Now it is time to apply it. To do this, we must know ourselves and gather information about our habits and processes.

I have been collecting information in Excel for 1 month and it has changed my life.

I will give you the simplest and most striking example: From Monday to Friday I make a trip that crosses the entire city and takes me 25 minutes. I could “add”, which in this case would be running to take less time, or I could “eliminate”, look for the shortest route to avoid detours. After calculating the route on Google Maps I saw that, in reality, I did not take the shortest route, it could save 4 minutes.

4 minutes of "muda" seems insignificant, but let me explain:

I make the journey twice a day, there and back, that's 8 minutes.

I make the journey 5 days a week, that is, 40 minutes.

I make the journey approximately 22 days a month, that is, 2 hours and 56 minutes.

Every month I have 3 extra free hours.

This is one case, but I have noted dozens like this. The end result has been that I save 1 hour and 10 minutes on average every day, in other words, it's as if the day had about 25 hours, I do the same as I used to do and I have 1 more free hour.

Improvement by elimination is undervalued, but it is very powerful for two reasons:

You don't have to investigate or innovate, you just need to gather information about your processes and quantify them in time, money, etc. On the other hand, to add improvement sometimes it is not obvious, it requires innovating, testing and seeing results.

With the same performance, you get more results. I don't do everything faster, I do the same thing I used to do, but I have 1 more free hour a day. It's powerful because without increasing your investment or effort, you achieve more.

Maybe you don't need to run faster, but to get rid of ballast.

✍️ It's your turn: Have you ever thought about the huge impact of eliminating what's holding you back? The tiny 4-minute change opened my eyes.

💭 Quote of the day: "Small changes in the path can make big differences in your destiny." Sean Covey in Seven Habits of Highly Effective Teens.

References 📚

Fuss, M., & Waverman, L. (1990). The extent and sources of cost and efficiency differences between US and Japanese motor vehicle producers. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 4(3), 219-256.

Fuss, M., & Waverman, L. (1991). Productivity growth in the motor vehicle industry, 1970-1984: A comparison of Canada, Japan, and the United States. In Productivity growth in Japan and the United States (pp. 85-108). University of Chicago Press.

Pareto, V. (1971). Manual of Political Economy. New York : A. M. Kelley. ISBN 978-0-678-00881-2

Pereira, R. (2009). The seven wastes. Isixsigma magazine, 5(5), 1-3.

Princenton University. (1990). The Decline of the U.S. TV Industry: Manufacturing. En Princenton University. https://www.princeton.edu/~ota/disk2/1990/9007/900709.PDF