Why we make bad decisions (and how to avoid it) (Part 1)

Distilling Books - Number 28

Welcome to Mental Garden. The following letter is part of our “Distilling Books” collection, in which we extract the most revealing ideas from literature. For the complete library, click here.

🏷️ Categories: Decision making and biases.

It’s happened to you before.

You made a decision that seemed right. Months later, you look back and think: How did I not see it?

It doesn’t happen just once. It happens many times. Work, money, relationships, projects. Different decisions, same ending: the uncomfortable feeling of having failed… without knowing where.

So you begin to doubt your intuition, your judgment.

But what if the problem isn’t you?

Today we’re talking about the book Decisive, by Chip and Dan Heath, experts in decision-making. The book starts with an uncomfortable truth: smart people also make bad decisions. And it’s not the exception.

It’s the rule.

Here you’ll see why we decide so poorly, the 4 invisible errors that sabotage our decisions, and why thinking harder almost never helps. The book is very high quality, so we’ll cover it in 3 parts to fully distill its essence.

Today we’ll look at: the diagnosis.

In the next two editions: the way out.

Because understanding the failure is the first step to fixing it.

This is going to be great—let’s dive in…

The problem lies in how we decide

The biggest mistake we make when deciding is assuming that a decision is an isolated act.

We think of decisions as single moments: accept the job or not, invest or not, stay or leave. The reality is that every decision is the result of an invisible process that starts long before the “yes” or the “no.” A mental process full of biased information, emotions, and unfounded assumptions.

When a decision goes wrong, we review the outcome. We rarely review the process.

And that’s where everything breaks.

When we fail, we think the bad decision came from lack of time, from not thinking through each option enough, or from the emotions of the moment. But Decisive dismantles this intuition with an uncomfortable idea…

Thinking more inside a bad frame doesn’t improve the decision—it makes it worse.

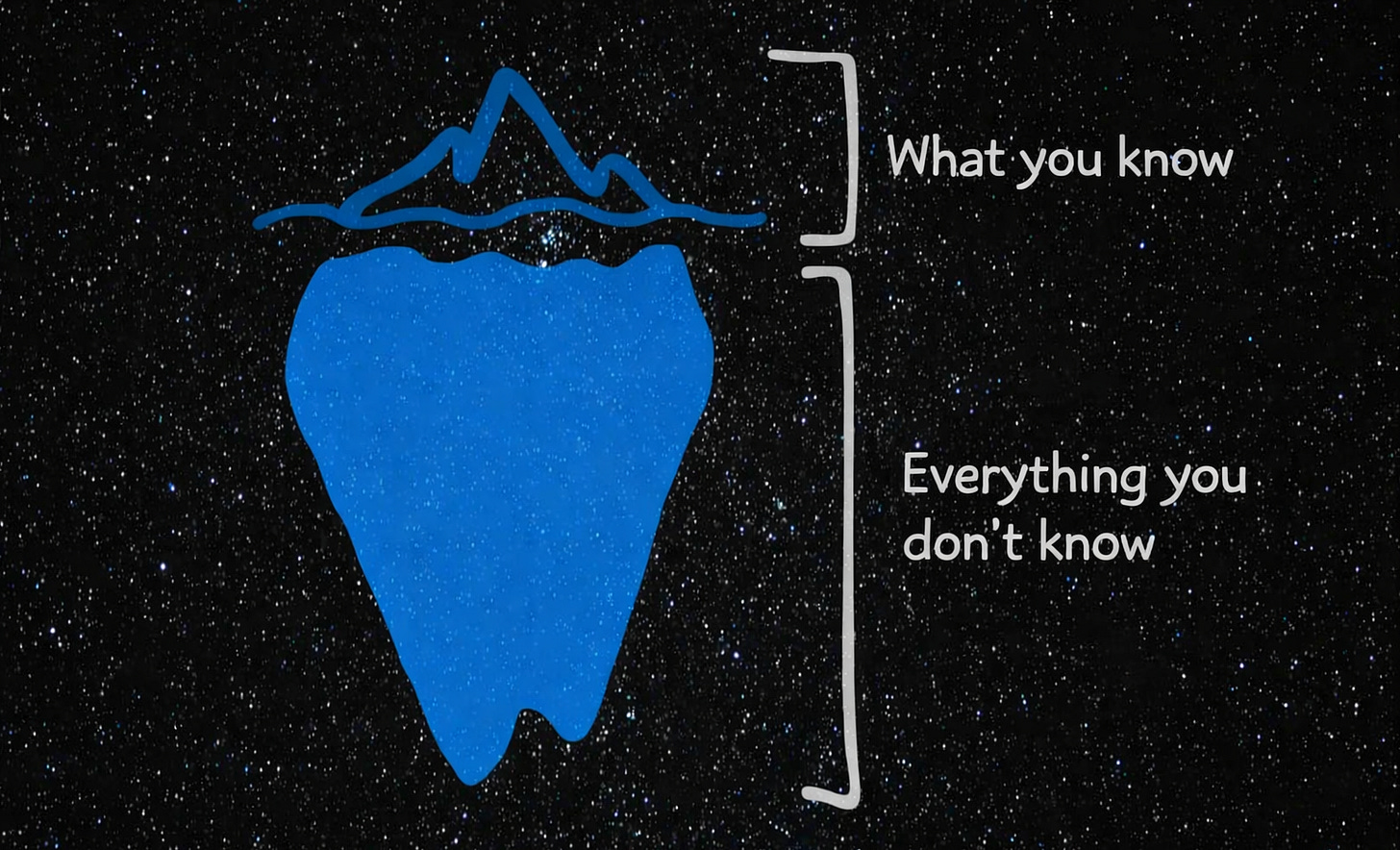

Because we’re not reasoning from scratch. We’re reasoning from a mental structure already conditioned by invisible biases. We don’t fail due to lack of intelligence. We fail because we think from a flawed framework without realizing it.

And that flawed framework has clear culprits…

Villain #1: Narrow framing

It all starts with a poorly framed question.

“Do I take this job or not?”

“Do I stay in this relationship or leave it?”

“Do I launch this project or scrap it?”

These questions seem reasonable, but they hide a trap: they reduce a complex reality to a false binary. Two options. One choice. End of analysis. Narrow framing eliminates options from the very beginning of the decision-making process, and when you can’t see all the options, you can’t choose them.

Narrow framing appears as soon as we feel pressure to decide.

The brain hates ambiguity. You want to close the problem quickly and get rid of doubt, so you unconsciously turn a complex situation into a simple question. This gives us a false sense of control that soothes us (and makes us fail).

On top of that, we tend to focus only on what’s right in front of us. On the immediate. The result is clear: we choose between bad and few options, believing there are no others.

And when you only see two paths, the next villain enters the scene…

Villain #2: Confirmation bias

Once you lean toward one option, your mind stops exploring.

It starts justifying.

You look for information that supports your preference. You ignore uncomfortable data that contradicts you. You minimize warning signs and opposing evidence. And we call all of this “thinking critically” or “evaluating.” This bias consists of believing you’re being objective when you’re no longer being objective at all.

It appears because the brain values internal consistency more than truth.

Being right—or sticking to your view—feels better than realizing you’re wrong and doubting yourself. And worst of all: the more important the decision, the stronger our need to believe we’re on the right path, which is why we cling to our ideas.

The problem is that we confuse investigating with confirming our belief.

And so, a bad option becomes increasingly solid… but only in our heads.

And despite all this, there are still two more villains to come…

Villain #3: Short-term emotion

Important decisions are rarely made in complete calm.

They’re almost always made with fear of loss, with a sense of artificial urgency, with attachment to a status quo we like, or with overflowing enthusiasm. Emotion doesn’t eliminate our ability to think, but it hijacks our sense of time.

The future becomes abstract.

The present weighs too much.

This happens because the human brain evolved to survive, not to plan twenty years ahead. Those are situations that only arise in stable moments of the modern, developed world. They’re not part of our evolutionary origin.

That’s why we overvalue immediate relief.

That’s why we postpone necessary but uncomfortable decisions.

That’s why we avoid present pain even if it harms us later.

We don’t decide thinking about who we’ll be in five years.

We decide thinking about how we feel today.

And that distorts everything.

But even if we manage to calm down, there’s still one last enemy left…

Villain #4: Overconfidence

We believe we understand the future better than we actually do.

We underestimate risks.

We think this time will be different.

We overestimate our chances of success.

Overconfidence feels like clarity. And that’s why it’s so dangerous. It happens when we confuse explaining with predicting. Being able to explain why something worked in the past doesn’t mean we can predict that it will work in the future. But the more expert we feel about something, the more we risk when predicting.

That’s why we believe our case is unique.

That’s why we believe this time will break the usual trend.

That’s why we think statistics don’t apply to us.

And so we make very risky decisions with crushing confidence.

The problem isn’t one villain. It’s all of them at once.

The real damage happens when these errors combine.

And that’s the norm.

Narrow framing limits options.

Confirmation bias reinforces a prior preference.

Short-term emotion drags you into short-term thinking.

And overconfidence removes caution because you feel like an expert.

The result is a decision made quickly, with conviction… and badly.

It’s not that you’re incompetent.

It’s that the system was broken from the start.

And here’s the key question… How do we change the system?

That’s what Decisive does: it provides a decision-making system that works despite how we humans are. A system that neutralizes biases before they can harm us.

That system is called WRAP, and we’ll analyze it in detail, step by step.

What comes next

In this first installment, we’ve made the diagnosis.

You’ve seen why we decide poorly.

Which errors repeat themselves.

And why it’s not a personal flaw, but a structural one.

In the next edition, we’ll dive deep into the transformative part: how to start making better decisions using the WRAP system, step by step.

Because understanding the problem changes awareness.

But changing the system changes results.

And that’s where everything starts to improve…

Here is the second part:

Want to know more? Here are 3 related ideas in the meantime:

Correlation vs. causation: a common mistake in understanding the world

The 10 most dangerous logical fallacies (and how to avoid them)

✍️ Your turn: Which decision from the past year would you see differently today… and which part of the “invisible process” do you think you failed to review?

💭 Quote of the day: “Success arises from the quality of the decisions we make and the amount of luck we receive. We can’t control luck. But we can control how we make decisions.” — Chip Heath and Dan Heath

See you in the next letter about Decisive! 👋

References 📚

Heath, C., & Heath, D. (2013). Decisive: How to Make Better Choices in Life and Work.

This is going to be a great series and I'm looking forward to it very much. But there's one thing that's always puzzled me: sometimes, not often, but rarely, for big decisions in my life, I seem to default to a subconscious level. I just "know" that a particular big decision is the "right" one. And it always has turned out that way. I'm talking about decisions like who to marry and what house to buy. Big decisions. Decided, on the surface, irrationally.

So I will be interested if that comes out at all in the Stoic approach. My guess is that it won't and that these questions are more along the lines of neoplatonism.

But great idea for a series~!