The tragedy of good fortune

Why the happiest moments leave us feeling empty afterwards

🏷️ Categories: Happiness.

Have you ever felt it… that strange emptiness that arrives after something exciting?

An unforgettable trip.

A promotion at work.

A personal achievement that once felt unreachable.

For a few days, everything seems perfect—you’re floating on a cloud, life has a special glow. You wake up energized, things flow, the world seems on your side. And suddenly, a slump begins to creep in. Everything turns gray again, monotonous, dull… And then comes the emptiness and the usual reflection:

A few weeks ago I was euphoric—where did all that magic go?

It’s the tragedy of good fortune.

The tragedy of luck

An explosion of good luck nearly always leaves behind an unexpected void.

Think of your last vacation. The excitement begins long before boarding the plane: you spend hours planning each spot, making reservations, dreaming about the landscapes, researching everything about your destination. The trip arrives and it’s even better than expected; everything goes perfectly. But on the flight back, as the plane touches down, a sadness settles in.

Everyday life now seems gray. It feels tragic.

The same happens after a job promotion, winning a prize, or reaching a personal milestone. The same happens to children every summer when they return to school after vacation. What once felt like sustained happiness becomes nostalgia, apathy, or anxiety.

The explanation lies in our brain: we adapt too quickly to the good.

Hedonic adaptation: the trap of getting used to things

Psychologists call it hedonic adaptation.

It’s the process through which intense emotions—both positive and negative—fade over time. Winning the lottery. Buying a new car. Moving into a new home. All of these create a spike in wellbeing… that evaporates in moments, returning us to our emotional “baseline.” The issue is that the process is uneven:

Negative emotions last longer than positive ones (Baumeister et al., 2001).

Our system is designed to never forget threats. Evolutionarily useful, but emotionally exhausting. The consequence is that after each stroke of good luck, the bar rises. What seemed extraordinary yesterday feels normal today. And what’s normal begins to feel poor, empty, gray, dull, monotonous…

The more you have, the more you want, and the less you value what you had at the start.

Adaptation level

You judge life events based on what you’ve become used to.

If you’ve always eaten stale bread from yesterday, a warm freshly baked croissant seems like a luxury. If you eat croissants every day, they quickly become routine and lose all excitement. Good luck suddenly pushes our reference point upward, making the slump during adaptation even greater.

And anything that doesn’t meet that new standard feels like a loss.

Lottery winners are not happier a year and a half after winning. In fact, they enjoyed ordinary daily pleasures—like drinking coffee or chatting with friends—less than those who didn’t win (Brickman et al., 1978).

Income has tripled for many developed countries over recent decades, yet average happiness hasn’t risen accordingly (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012). This is the Easterlin Paradox: more money doesn’t equal more happiness once you reach a middle-high income level (Easterlin, 2006).

Silver Olympic medalists are less happy than bronze medalists because they compare themselves to what “could have been” (the gold), while bronze medalists compare themselves to what they “avoided” (no medal at all). One event, two perspectives. How you interpret something determines whether it feels satisfying or disappointing (Medvec et al., 1995).

In these and many other cases, good luck ends up working against us.

The happy forecast bias

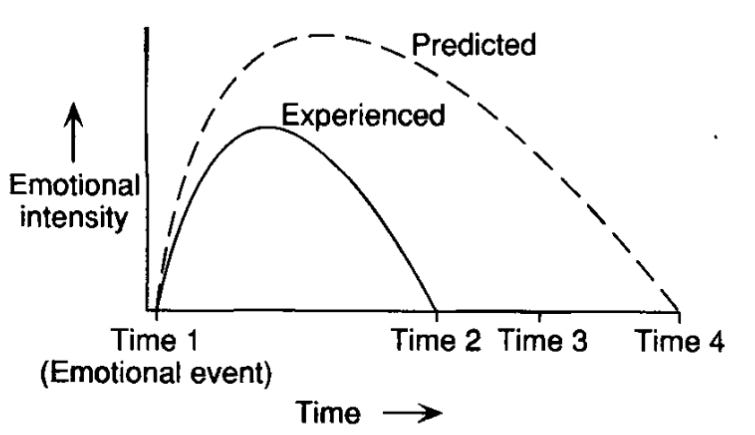

We overestimate how much—and for how long—an event will make us happy.

We think: “If I get this job, I’ll be happy.” We picture it as a permanent, unchanging state. Every day perfect, every day just as bright. In our mind, everything is idyllic. But reality is less poetic: the excitement lasts weeks, sometimes days, and although it may improve our mood, life inevitably brings back its ups and downs (Wilson & Gilbert, 2005).

We fail to anticipate how quickly the extraordinary becomes ordinary.

That emotional drop pushes us to chase the next novelty to fill the void.

Buying something new, traveling to a different place, trying the newest trend. We do it because we confuse novelty with happiness. It’s a mirage: we buy simply for the feeling of having something new. And slowly we fall into a consumerist spiral that never satisfies—because novelty is the most fleeting thing of all.

But here’s what does bring more stable happiness…

Activities vs. circumstances

Intentional activities matter far more than external circumstances.

On average, your daily habits, personal projects you’re passionate about, and social relationships have four times more impact than one-off life events like moving homes, buying a car, getting a promotion, or winning the lottery (Lyubomirsky, 2010).

In other words: sustained happiness comes from what we do every day.

Learning, creating, connecting…

How to escape the tragedy of good fortune

Science points to several possibilities:

1. Cultivate gratitude

Gratitude is an antidote to adaptation.

When you take a few seconds at the end of the day to write three good things that happened, your attention shifts from what’s missing to what’s present. And the more you train this habit, the more natural it becomes to enjoy the small things: the smell of coffee, shared laughter, a ray of sunlight entering through the window.

It’s the lesson behind Perfect Days, a film that changed my life.

2. Intrinsic goals

Money or fame always fall short because we adapt instantly.

But growing, learning a new skill, contributing to a cause, or helping others are self-reinforcing: each new step brings new gratification. When motivation comes from within, the process becomes more rewarding than any final outcome.

That’s why the process is infinitely superior to the goal.

3. Build close relationships

People aren’t objects—they change, surprise you, challenge you.

It’s very easy to get used to an object, not a person. Cultivating bonds is the best way to ensure stable happiness. No mansion or medal compares to the richness of a deep friendship. A car will always be the same; a person opens an infinite world of plans and conversations and, best of all, will be there when you need them most.

The tragedy of good fortune is a mirror of who we are.

It’s not the trip, but how you savor it.

Not the medal, but what you compare it to.

Not the stroke of luck, but the ability to enjoy it without expecting everything to be like that.

✍️ Your turn: What daily habits bring you the most satisfaction in life? Which others could you cultivate?

💭 Quote of the day: “Most likely, someday we’d simply run out of luck.”

— *Gene Kranz, Failure Is Not an Option

See you next time! 👋

References 📚

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is Stronger than Good. Review Of General Psychology, 5(4), 323-370. URL

Brickman, P., Coates, D., & Janoff-Bulman, R. (1978). Lottery winners and accident victims: Is happiness relative? Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 36(8), 917-927. URL

Easterlin, R. A. (2006). Life cycle happiness and its sources. Journal Of Economic Psychology, 27(4), 463-482. URL

Medvec, V. H., Madey, S. F., & Gilovich, T. (1995). When less is more: Counterfactual thinking and satisfaction among Olympic medalists. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 69(4), 603-610. URL

Lyubomirsky, S. (2010). Hedonic Adaptation to Positive and Negative Experiences. URL

Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2012). The Challenge of Staying Happier. Personality And Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(5), 670-680. URL

Wilson, T. D., & Gilbert, D. T. (2005). Affective forecasting. Current Directions In Psychological Science, 14(3), 131-134. URL