Kant, the defendant and the judge: The categorical imperative and the silver rule

Notes on giants - Number 7

Welcome to Mental Garden. The following letter is part of our "Notes on giants" collection, in which we explore the thoughts of humanity's greatest minds.

To see the full library, click here.

🏷️ Categories: Literature, Mental models, Behavior.

Today

is with us. Javier is passionate about critical thinking and philosophy, that's why I proposed him to collaborate for this edition.We will talk about Immanuel Kant and his categorical imperative.

Kant is one of the most influential thinkers of the West, but the difficulty of his reading makes him sometimes forgotten by many. But here is the key point: the categorical imperative we will talk about today is not a useless and boring theory.

It is a practical compass for your daily decisions.

It's about acting according to universal principles of justice. If you truly aspire to be a role model and align your values with your actions, you will now see how to do it.

As is well known, Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) is recognized as one of the most influential philosophers of the Enlightenment and of the history of Western thought. His main philosophical contribution is embodied in his critical work, where he proposes that human reason establishes the conditions of experience and knowledge. With this, he sought to overcome skepticism and dogmatism, proposing that there is a limit to what we can know, while human understanding, in turn, determines with its categories how we are able to perceive and organize reality. But if there is one area in which Kant stood out, it was in the moral sphere, where he developed deontological ethics par excellence, that in which action is valued for its conformity to the universal moral law and not for the consequences that derive from it. This approach emphasizes the pure intention to act according to a rationally recognized duty.

The aspiration to achieve a formal and universal ethics was an obsession for Kant, to which he devoted himself rigorously. A famous anecdote that highlights his methodical character tells that the citizens of Königsberg adjusted their watches according to the schedule of their daily walk. Kant was so punctual and constant in his routines that his behavior served as a “human clock”. Whether apocryphal or not, the anecdote serves to symbolize his commitment to base morality on objective and universal principles, separate from personal preferences or changing social customs. To this day, his thought is considered fundamental to understanding modern ethical reasoning and the autonomy of the subject as the basis of moral law. There was something of a break with the past in Kantian boldness. But both its plausibility and that break are still in dispute.

Formulations of the categorical imperative

Kant introduces the concept of the categorical imperative as the cornerstone of his ethics. A categorical imperative is an unconditional command that applies to all rational beings, regardless of their concrete desires or ends. The key is that, for Kant, the fulfillment of moral duty cannot be subordinated to personal gain or utilitarian considerations; it must be obeyed only by virtue of the rational recognition that it is a universally valid command.

The philosopher presents three formulations that he considers equivalent.

The first formulation commands “Act only according to such a maxim that you can will at the same time that it becomes a universal law”.

The second states “Act in such a way that you use humanity, both in your person and in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end and never only as a means”.

Finally, the third states “Act as if by means of your maxims you were always a legislating member in a universal realm of ends.”

Although each emphasizes different aspects, Kant insists that all three formulations describe the same moral requirement of universality and respect for human dignity. But their different formulations generated misunderstandings that Kant was quick to refute. In fact, in the evolution of his works, one of them ended up taking precedence in order to emphasize this uniqueness. Today, however, they continue to be the subject of discussion. There are authors, such as Javier Muguerza, who have wanted to continue identifying in one of them a specific imperative, capable of legitimizing ethical and civil disobedience, an imperative of dissidence. Because rights have been won through conflict, and not through acquiescence to the already recognized or even consensual right.

But in the face of the formality and abstraction of this imperative subject to interpretation, the nuances and clarifications that Kant was forced to make were even greater. Precisely for those who simplified it as a new formulation of an old trivial rule.

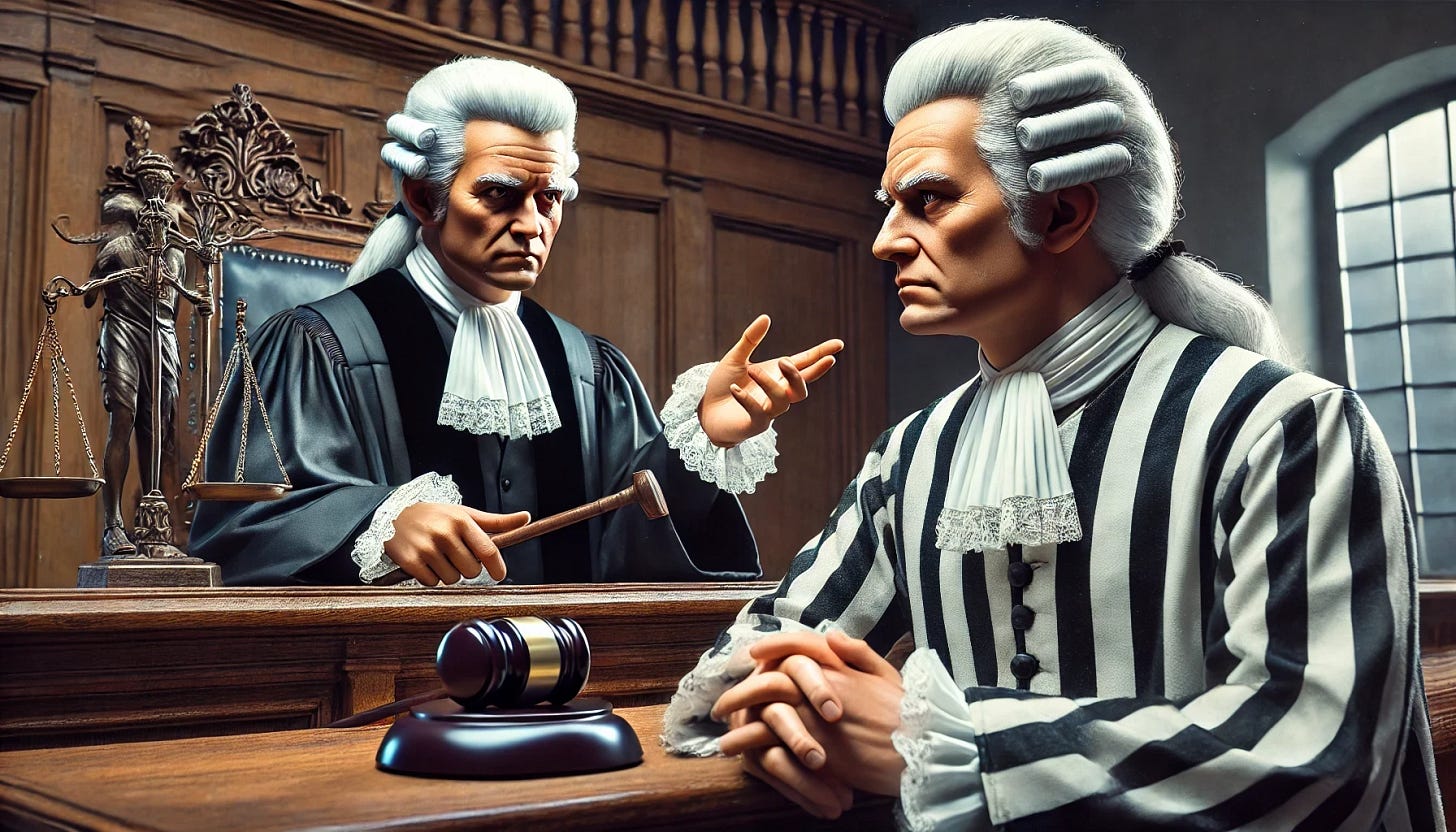

The defendant, the judge and the trivial rule

One of these interpretations was to make Kant's categorical imperative an equivalent of the so-called “golden rule” or, in its negative formulation, the “silver rule”, to which Kant explicitly alluded in order to dissociate himself from it in his work Foundation of the Metaphysics of Morals. The so-called “silver rule” comes from the ancient formula: quod tibi fieri non vis, alteri ne feceris (what you do not want for yourself, do not do to others).

Kant rejects that his imperative is a new formulation of this old principle which he calls “trivial”. According to his analysis, the silver rule remains a prohibition against causing harm or evil to others, but does not achieve the aspiration of founding a universal principle of moral action. In other words, the formula “do not do to another what you would not want done to you” can be interpreted as an ethics of abstention, while Kant, on the contrary, proposes a positive and universally valid moral law, without depending on empathy or direct reciprocity. Despite this, there are many authors who reiterate this formula to explain this pillar of Kantian ethics. Some consider them to be unfortunate formulations under the alibi of an informative interest, which only produce confusion.

To explain this difference, in a footnote, Kant argues that the criminal could oppose the same old principle to the judge who is about to punish a defendant: that he should not do to him what he would not like to be done to him. In contrast, the Königsberg philosopher argues, the criminal could never argue something similar with the categorical imperative that preaches the universality of the maxim of conduct: even if the judge would not like to have to endure a penalty, he would no doubt also think that he should abide by a universal law that every criminal must receive a consequent punishment for having committed a crime.

But... is it possible to make another interpretation different from Kant's interpretation of this millenary ethical principle?

An age-old principle

The Golden Rule is a cross-cultural principle commonly expressed as “treat others as you would have them treat you”. This maxim is present in numerous religious and philosophical traditions. In ancient Egypt, it begins to be reflected in teachings such as those of Ptahhotep, while in ancient India, in both the Sanskrit and Tamil traditions, similar formulations are found. Tradition attributes some formulation to Confucius in China, or to Pythagoras and Epictetus in Greece. In Persia, Zoroaster promoted it, while it was echoed by Seneca in Rome. From Christianity, through Confucianism, to Islam and Judaism, it is present in some form. Its versatility and its extension throughout history demonstrate its intuitive appeal and its ease of communication. Apparently, like the silver rule, the golden rule also seems to focus on reciprocity: the subject's action depends on what the subject would like to receive.

Indeed, in many of these philosophical and religious traditions, the norm is often shielded by the design of the divine will or the universe that promises to reward or threatens to punish behavior, leading to what is desirable. In contrast, in the Kantian system, the moral law emerges from autonomous practical reason, placing respect for human dignity at the center and not depending on any external authority.

Is it possible, however, for Kant to make a somewhat simplified reading of the silver rule? Returning to his example of the judge and the prisoner, this millenarian principle could be translated as meaning that if the prisoner asks the judge not to send him to prison because the judge would not want to suffer that penalty in his place, the judge could argue that he would be willing to suffer that penalty if he had committed the crime that the prisoner has perpetrated. That is, the judge does what he would want to be done to him, i.e., judge him justly, and does not do what he would not want to be done to him, i.e., judge him unjustly. Contrary to what Kant said, perhaps this millenarian maxim is no more trivial than its imperative, if it is not interpreted trivially, but at bottom it evidences the shortcomings of Kantian ethics when it is based only on rational deliberation in solitude. This is what is usually known as the problems of Kantian monological reason.

The problems of monological reason

Despite the internal coherence and rationalist force of the Kantian system, its difficulty in endowing the moral law with concrete content has been criticized: Kant's formal ethics runs the risk of remaining in abstraction, since it limits itself to a demand for universality without determining what specific ends or values should be promoted. This problem has been described as Kant's “monological reason”, a reason that reflects alone and does not necessarily integrate the different perspectives and real needs of society.

In the 20th century, philosophers such as John Rawls and Jürgen Habermas proposed pragmatic solutions to overcome this limitation.

Rawls, building on Kant's universal aspiration, proposed his idea of the “veil of ignorance”: this idea suggests a hypothetical procedure in which, by ignoring our personal characteristics (social position, abilities, etc.), we would agree on impartial principles of justice. Let us discriminate what rules we would want to govern a society, and then see what place we would occupy in that society.

Habermas, on the other hand, showed the need to open Kantian deliberation to the public space of dialogue. The communicative dimension of ethics is essential, and so he proposes a “dialogical reason” based on participation and consensus in the public space through dialogue and rational debate. We tend to tend to be right in soliloquy. There is no solitary deliberation that resists an openness to such dialogue.

Both initiatives are indebted to Kantian ethics, but they seek to complement the universal principle of the categorical imperative with inclusive and participatory procedures that make it possible to concretize morality in a fairer and more pluralistic way in real contexts.

Returning to Kant's example of the prisoner and the judge, the millenarian silver rule seems to open us fully to the approaches of Rawls and Habermas: Judge and prisoner, without knowing what role they are going to play, could have sat down to decide what the law that a judge would apply to a prisoner in the face of a crime should be, without prejudice or coercion. More than one implacable judge, absorbed by his own certainty, would have overlooked his excesses of severity without taking into account the defendant's point of view. And, call me naïve, but I believe that some defendant would have reconsidered and at least objectified his own self-justifications in the face of such an approach, recognizing the legitimacy of a judge's reasoning. But who am I to make amends to Kant.

What do you think?

References 📚

Kant, I. (1785). Fundamentación de la metafísica de las costumbres. Traducción recomendada: García Morente, M. (Ed.). Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

Muguerza, J. (1984). La razón sin esperanza. Barcelona: Crítica.

Rawls, J. (1971). A Theory of Justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Habermas, J. (1981). Teoría de la acción comunicativa. Traducción: Jiménez Redondo, M. (1997). Madrid: Taurus.

It seems to me, Ethics comes before the laws, not after or at the same time. And I think, laws should be translations of it (because laws establishes concrete penalties in the context of a particular society, and because not always a law serves the best for a society...).

Ethics exists in the realm of the individual, while laws are established in the collective.

Fortunately or unfortunately, it seems the real ethical questions are to be discussed in a monological context, until the human beings evolve towards sharing their individual consciences.