🏷️ Categories: Mental models, Decision making and biases, Continuous improvement.

This is the agenda of the day of a committee in charge of approving projects:

Construction of a nuclear power plant at a cost of 10,000,000€.

Construction of a bicycle parking shed that will cost €350.

Approval of a budget of €21 for office coffee.

It is 9:00 a.m. and there is no time to lose, they start with the nuclear plant.

At 9:30 the nuclear plant project was approved and they moved on to the next topic: the bike shed. This issue generated more discussion and modifications to the project were requested; it was resolved around 11:00 a.m. The committee then moved on to the bike shed issue. The committee then moved on to the issue of coffee for the office, which led to an intense debate that, after 3 hours of negotiations, was finally resolved at 2 p.m. with a unanimous decision.

Nuclear plant: 30 minutes.

Bicycle shed: 1 hour and 30 minutes.

Coffees for the office: 3 hours.

How is this possible?

Law of Triviality

You may remember Parkinson's Law, the law that says that work expands over time until it takes up all the time available to do the task. Funny thing is, Cyril Parkinson observed another strange pattern in human behavior.

“The time we invest in a matter is inversely proportional to its importance.”

Let's go back to the committee's story and you'll understand what happened.

The committee put the nuclear plant proposal on the table:

The issue was too complex to deal with in a single meeting; they needed weeks of discussion just to modify minute details.

Almost no one was an expert in nuclear physics and engineering; the discussion was dominated by two people while the others listened.

One of the experts proposed a modification that was rejected as too costly in time and money because it did not compromise the safety of the plant.

Next, the committee reviews the issue of the bike shed:

Everyone felt able to weigh in on the shed, as it was understandable and easy to make proposals, which lengthened the conversation.

The decision had minimal impact on the budget, but each person had ideas on how to save costs and improve the design, it's a simple issue.

Finally, the committee addressed the coffee budget:

The simplicity of the topic produced too many opinions from the committee, so there was a long discussion to get everyone on the same page.

The brand, type of coffee and coffee machine were debated for 3 hours.

The more mundane a topic is, the more knowledge we tend to have and the more our point of view is formed. As a result, we spend most of our time on insignificant issues and get sidetracked from the essentials (Descamps et al., 2021).

Strategies to avoid the law of triviality

1. Focus on the essentials:

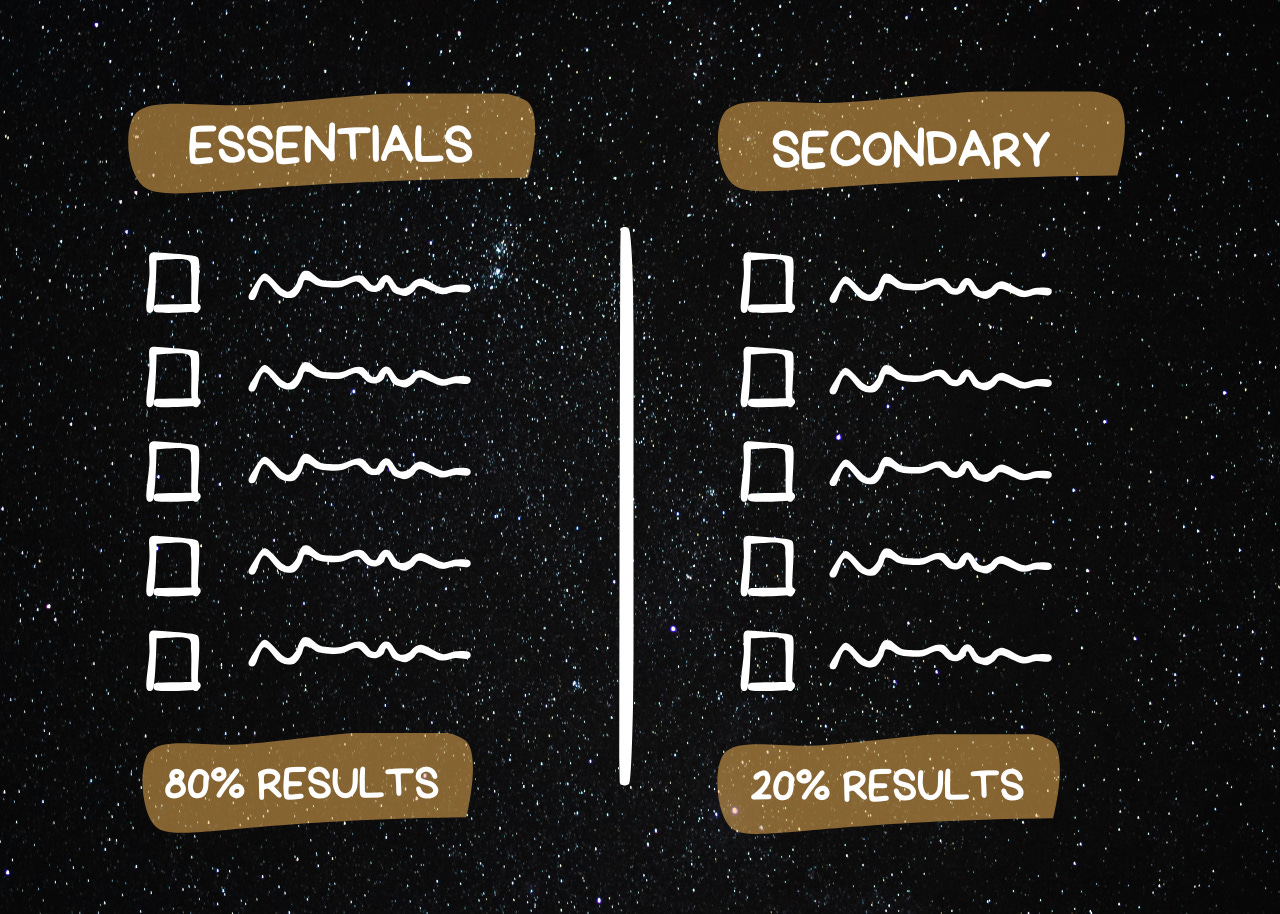

Make a list of all the tasks and decisions in your plan and divide them into essential and secondary. Always prioritize the essential ones.

In writing, for example, the essential task would be to develop the habit of writing daily and learn techniques to improve written expression. Secondary is deciding the time to publish or the ideal design of the Substack. No matter how beautiful my Substack is, without texts it is nothing.

5 essential tasks can be 80% of your final result.

5 secondary tasks can be 20%.

Use this approach for any other area of life.

Choose where you want to prioritize your time.

2. Avoid diminishing returns:

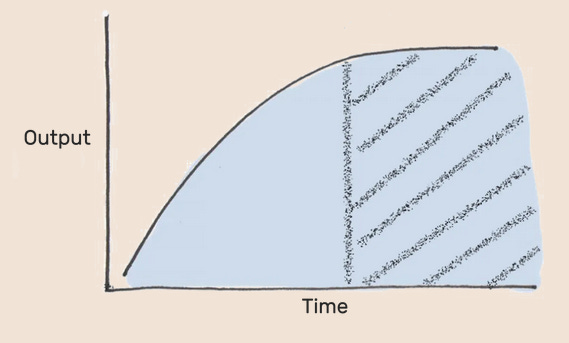

All tasks and decisions have a limit, you can't get to 100%. The more you improve something, the more effort it takes to improve it and the smaller the improvement.

No cook could cut without a knife.

All cooks could cut with a knife of average quality.

Only the best cooks could notice a change in their business performance by using a top quality knife.

Do you see the trend?

A basic knife makes a big difference, but the better the knife, the less it will impact the results. Only an expert chef could get the full potential out of a top-quality knife; for most, upgrading will be a waste of money. You have had to improve the essentials too much for such a minor issue to make a difference.

There is a critical point at which an aspect is no longer worth improving.

That's the moment that tells you it's time to move on to the next task. This is a matter of observation. You must observe when your efforts stop producing substantial progress in your decisions or results. If we go back to the example of the committee:

Deciding whether the roof of the bike shed should be blue or green is absurd.

Spending days looking for a design that will reduce costs by 5% when the budget allocated to that task is minimal is also absurd.

If the design is done and meets reasonable expectations, you're done.

Perfectionism kills progress.

The more time you spend on minutiae, the more you delay the actions that will move you forward.

3. Reduce the number of participants:

If you are going to make a group decision, avoid this silly mistake.

In meetings, everyone wants to participate, but not everyone has a strong and valuable opinion. Thus, the more people there are, the more time is wasted on superfluous ideas and the less time is left for listening and debating with the people who are the most expert on the topic (Parker, 2018).

Meet with the smallest, most select group possible.

We are not looking for seas of opinions, but drops of wisdom.

✍️ It's your turn: Have you recently gotten into something only to realize you've been wasting hours of time?

💭 Quote of the day: “The basic question is what we do within the time we are given: how we plan, decide, organize, evaluate, and review our tasks.” Charles E. Hummel, Freedom from Tyranny of the Urgent.

See you soon! Take care and focus on what's important 👋.

References 📚

Descamps, A., Massoni, S., & Page, L. (2021). Learning to hesitate. Experimental Economics, 25(1), 359-383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-021-09718-7

Parker, P. (2018). The Art of Gathering: Create Transformative Meetings, Events and Experiences. Penguin UK.

Parkinson, C. N. (1965). Parkinson’s Law, Or, The Pursuit of Progress.