Small things and their big implications

The inventor's paradox: For small problems, huge solutions

🏷️ Categories: Mental models, Continuous improvement, History.

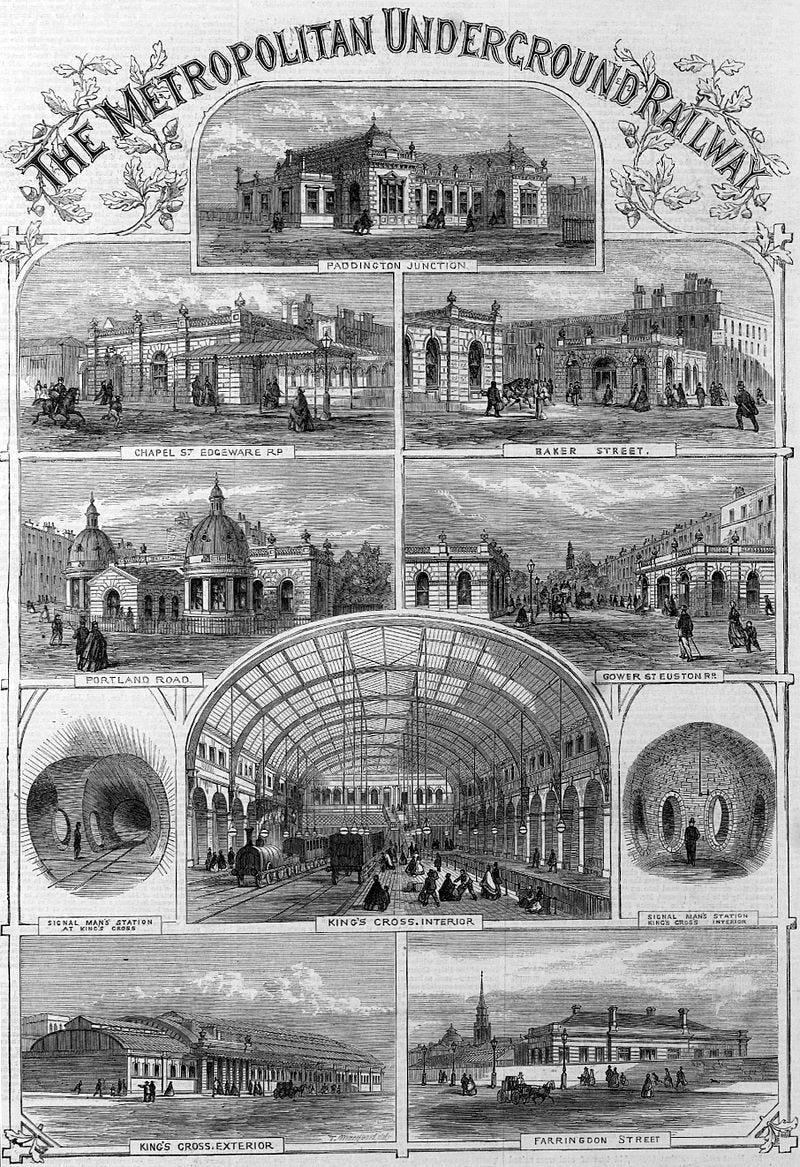

London, mid-19th century.

The streets are crowded.

Carriages, horses and pedestrians compete for space in a city that is growing at a dizzying pace. Every day, thousands of workers arrive in trains at outlying stations and saturate the urban roads to reach the center. A solution had to be found, and for many people it was to build more roads and train lines.

For many people, not all.

Charles Pearson, a lawyer and social reformer, looked at the problem on a different scale.

The question was not “How do we eliminate traffic jams?”, the question Charles Pearson believed really needed to be asked was “How do we design a good urban mobility system?” The real challenge was to efficiently connect the suburbs to the heart of the city, allowing commuters to easily move back and forth to avoid the overcrowding and congestion of the urban center.

Notice the difference in approach:

For most, the solution was very concrete: more rail lines and widening the streets.

For Charles, the solution was large-scale: redesigning the urban transportation network.

In 1845, he proposed the idea of a subway railroad linking outlying stations to the center. At first the proposal was ignored and the solutions proposed by the majority were tried, but everything was a failure. In the end, in 1854, the construction of the first line of the Metropolitan Railway was approved (Wolmar, 2005).

The world's first subway railroad.

Time proved Charles and his large-scale vision right.

The inventor's paradox

Charles was a visionary in seeing the problem on a broader scale.

The lack of a good transportation network was the problem, not traffic jams, specifically. Looking for solutions to traffic jams was putting a patch on a hemorrhage, the problem would reappear and become more severe as London grew bigger and bigger. This is what is known as the inventor's paradox (Pólya, 1971).

Sometimes, in order to solve a particular problem, we have to look for a large-scale solution that solves that problem and prevents the emergence of many others.

When we focus on solving a very specific problem, we are ignoring the overall context. If we addressed the problem on a large scale, we would find better solutions and could even go back to the original causes. The gridlock was just a manifestation of the real problem: an outdated transportation system.

The problem is not how to prepare for an exam on short notice. The real problem is how to adopt study habits that save you from studying under pressure at the last minute in the future.

The problem is not how to get out of the creative block that is keeping you from writing this week. The real problem is how to establish a consistent writing routine that will allow you to generate ideas and move your project forward in the long run.

The problem is not how to lose weight before summer. The real issue is how to change your eating and exercise habits to have a better quality of life and life expectancy for the rest of your life.

When you see life with a magnifying glass, you completely lose perspective of the world.

Think anti-fragile

Short-term solutions sabotage your long-term progress.

Instead of anticipating events, we tend to look for solutions when everything is about to collapse, or worse, when everything has already collapsed. It is like a wound; the analgesic will temporarily eliminate the pain, but the wound must be healed and we must learn from the experience to prevent similar wounds in the future.

Nassim Talem's concept of antifragile serves us well in these situations (Taleb, 2012).

Antifragile is that which improves with chaos, uncertainty and disorder.

Opt for antifragile solutions, look at what happened to me a few years ago....

When I started studying self-taught, I only read books, but soon forgot what I read; a waste of time. Then I started to underline what I read, but I saw that finding information among so many pages was not practical. So I tried making outlines in a notebook, but when I had read about 50 books, the amount of notes and outlines became overwhelming.

The problem?

Fragile solutions.

The solution?

The more content I add, the more the ideas reinforce each other, the more quantity does not make it worse, it makes it better. It is a system that approves of chaos.

Here's how you can adopt the anti-fragile mindset:

Identify the problem and broaden your vision: If you're studying on your own, don't do what happened to me. The question wasn't “How do I remember better?” it was actually, “How do I make an effective system for long-term studying?”

What is really generating this problem?

Is the problem a consequence of something bigger?

Make it anti-fragile: The more adaptable the solution, the faster you will overcome obstacles. A good way to find anti-fragile solutions is to look at the Lindy effect. The longer something has lasted, the more likely it is to be reliable.

Will it work well in 5 days? What about 5 months? What about 5 years?

Will it work well with 5 books? What about 50 books? What about 500? (That was my mistake).

What guarantees that this solution will continue to work? What does it depend on?

If you notice, in the short term, all solutions seem equally valid, but in the long term everything tends to get more and more complicated and the future becomes uncertain. Memorizing, bubbling, outlining, using zettelkasten... anything goes in the short term, but not when you have read 5000 books.

Think about other aspects of life.

In this changing and unpredictable world, being future-proof is crucial.

Be anti-fragile.

✍️ It's your turn: Have you ever had to resort to a broader solution to solve an everyday problem? That's how I got to the Zettelkasten, by stumbling over and over again.

💭 Quote of the day: ″The more people look for quick fixes and focus on acute problems and pain, the more that same focus contributes to underlying chronic illness.″ Stephen R. Covey.

See you next time! 👋

References 📚

Pólya, G. (1971). How to Solve it: A New Aspect of Mathematical Method.

Taleb, N. N. (2012). Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder. Random House.

Wolmar, C. (2005). The subterranean railway: How the London Underground was Built and how it Changed the City Forever. Atlantic.

This is an excellent read. You offered some helpful tips, especially for procrastination, so that you aren't faced with cramming information at the last minute and possibly triggering anxiety. You addressed healthy eating habits to enjoy a better quality of life. And for writers, you talked about how adopting a routine helps you be more consistent, generate ideas, and become more successful in writing. I love the quote you shared, “The more people look for quick fixes and focus on acute problems and pain, the more that same focus contributes to underlying chronic illness.″ Stephen R. Covey. Thanks for sharing.