The lesson of the sage Zhuang Zi to master any skill in life

Notes on giants - Number 13

Welcome to Mental Garden. The following letter is part of our "Notes on giants" collection, in which we explore the thoughts of humanity's greatest minds.

To see the full library, click here.

🏷️ Categories: Deliberate practice, Continuous improvement, Literature.

Over 2,000 years ago, a Chinese sage named Zhuang Zi wrote what we now call the “Book of Zhuangzi,” a compilation of philosophical tales about Taoism—an Eastern philosophy that emphasizes the value of living in harmony, without forcing rhythms or imposing control. Yin and yang, balance, and eternal duality.

In his book, I found a story that was a true revelation for me.

It’s the story of Cook Ding, a humble cook who, through his craft, reveals the secret to mastering any skill in life.

Here begins an age-old story…

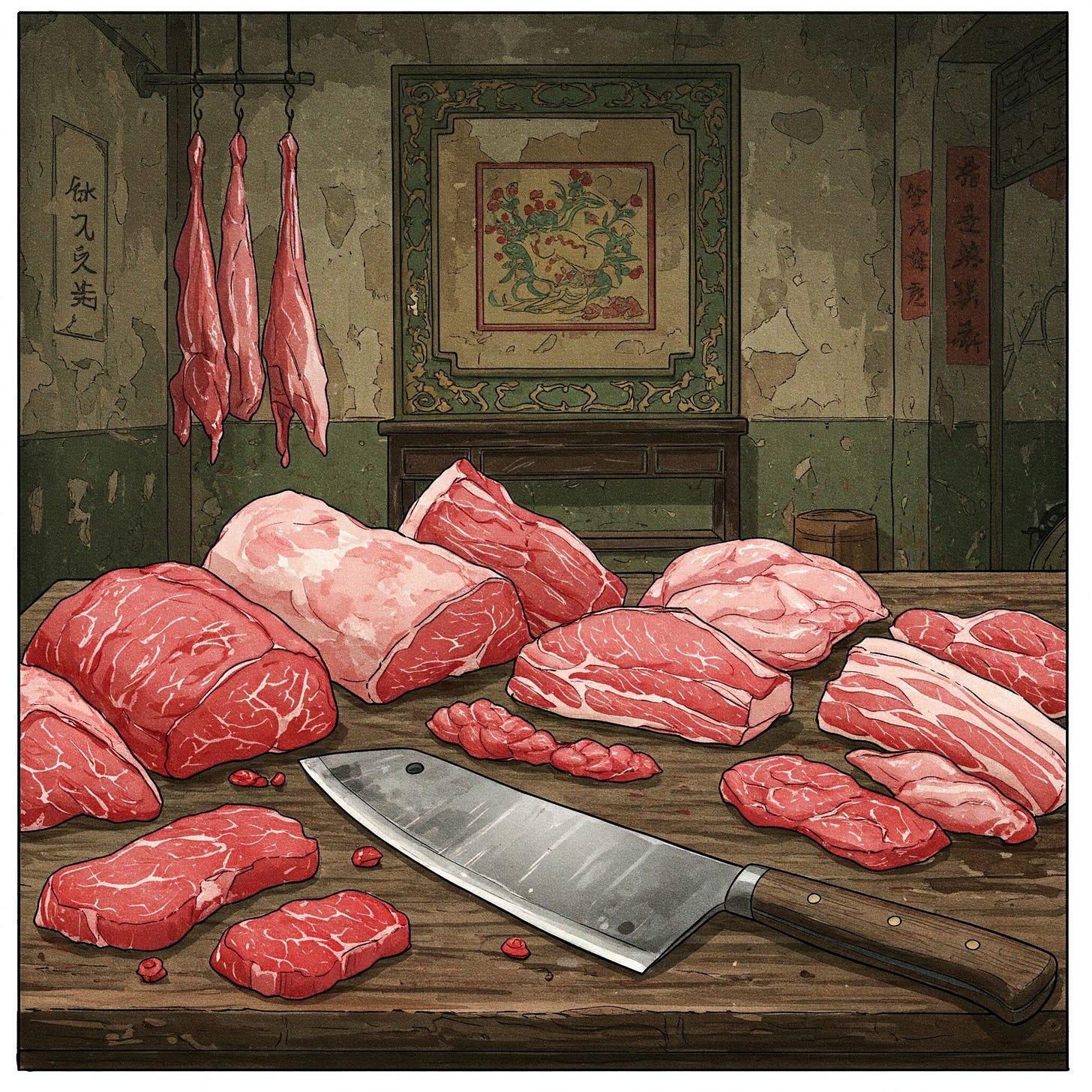

Cook Ding was carving up an ox for Lord Wen Hui. His hands touched the flesh, his shoulders pushed, his feet pressed, his knees followed. You could hear the slicing and crunching sounds. His knife moved with precision, everything unfolding like a harmonious melody. His movements matched the rhythm of dance and music.

Lord Wen Hui exclaimed:

—Incredible! How did you reach such a high level of skill?Cook Ding set down his knife and replied:

—What I do is not just technique—it’s much more than that.When I first started carving oxen, I saw the whole animal. After three years, I stopped seeing it as a whole and began to perceive its internal structure. Now, I trust my intuition rather than my eyes. My senses rest, but my spirit is active. I follow the natural path of the ox’s body: I cut through the large spaces, glide the blade between joints, and let it flow with the animal’s natural layout. I never cut through where the tendons and bones are tangled, much less through the thick bones.

A good cook replaces their knife every year because they cut through flesh.

An average cook replaces theirs every month because they hit bones.

I, on the other hand, have used this knife for nineteen years and have carved thousands of oxen. Yet, the blade is still as sharp as new.The ox’s joints have spaces, and the blade of the knife is extremely thin. By inserting something thin into a spacious area, the blade moves smoothly. That’s why my knife remains intact after so many years.

Still, when I encounter a tricky tendon or difficult joint, I pause and examine it carefully. I focus, slow down, and move the blade with precision. Suddenly, the ox comes apart effortlessly, as if the meat simply falls to the ground on its own.

Then, I hold the knife, look around in satisfaction, clean the blade, and put it away with reverence.

Lord Wen Hui exclaimed:

—Marvelous! After hearing your words, I understand the art of nurturing life.—“Cook Ding Carves an Ox,” Zhuang Zi

Mastery is flowing with what you do

What amazed the king wasn't Ding’s dishes, but how he moved the knife.

Every cut was fluid, precise, effortless.

When the king asked how he had achieved such mastery, Ding replied that at first, he only saw the ox as a whole. But over the years, he began to see its structures and no longer needed his eyes—he could cut without thinking.

It was easy. He didn’t cut the meat with force; he let the knife follow the shape of the ox.

The secret wasn’t strength, nor speed—none of that. The only secret was understanding the anatomy of the ox perfectly and knowing how to use the knife. Instead of forcing cuts with heavy blows like all the inexperienced cooks did, Ding simply followed the direction of the animal’s tissues.

He allowed his tool to move without resistance. Letting it flow.

Mastery is achieved by understanding the concepts and flowing with them—not by resisting them.

In business, successful people don’t fight the market; they understand its movements and adapt intelligently to changes.

In sports, elite athletes don’t train themselves into exhaustion; they make the most of each session and maintain a balance between nutrition, sleep, and exercise.

In science, the goal isn’t to impose preconceived ideas; it’s to study concepts and analyze data to reach conclusions. Truth reveals itself. It emerges.

The power of deliberate practice

Ding took years to stop seeing the ox as a whole and start seeing its structure.

Achieving mastery in any skill demands patience and deliberate practice, which means staying fully focused on what you’re doing, with a clear goal in mind, repeating the process again and again, always looking for ways to improve. These are the ingredients for mastery (Ericsson et al., 1993; Gladwell, 2009).

This goes against what many people chase today.

In modern life, we constantly seek instant gratification—quick results and immediate rewards. If something doesn’t change overnight, we think it’s not working and look for shortcuts—or worse, we give up.

Everyone would love to cut with Ding’s skill.

Almost no one is willing to commit like Ding did.

You have to be willing to dedicate years and years to one single thing, focusing on just that. Ding was a cook—he wasn’t a cook, poet, writer, and musician. It’s simple math: you can be good at many things, but excellent at very few.

Reaching the flow state: Zero mind

One of the deepest parts of the story is when Ding says he no longer uses his eyes to cut—the spirit guides him.

This isn’t mystical, but psychological. In modern psychology, it’s known as the flow state, and you’ve experienced it, even if you didn’t know the name (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975). It’s when you’re so focused on an activity that time seems to disappear, everything flows naturally, and your performance peaks.

You flow completely with the activity—nothing external affects you.

To reach this state, deliberate practice and total focus on what you’re doing are essential. Ding reached it every time he carved: his mind disappeared, and only the pure act of cutting remained. No effort, no thought—just the action.

After years of practice, all he had to do was move—he had mastered it all.

This is how mastery is achieved: practicing until the skill becomes part of you. Until, like Ding, you can glide your knife with precision without even thinking. Focused on improving for hundreds of hours, fully attentive to the task, eager to do it even better the next time.

That’s when you begin to flow.

That’s when your performance skyrockets.

✍️ Your turn: What activities put you in a flow state?

After 10 or 15 minutes of writing, I enter that state and suddenly the words just flow—everything writes itself effortlessly.💭 Quote of the day: “Do not do good to seek fame, nor do evil to avoid punishment. Follow the natural path and balance your life with it: this way you will preserve your body, maintain your essence, care for your parents, and live your life to the fullest.” — Zhuang Zi

See you next time! 👋

References 📚

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond Boredom and Anxiety. Jossey-Bass.

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406.

Gladwell, M. (2009). Outliers: The Story of Success. Penguin UK.

Excellent article. It inspires me to pursue my piano practice with greater focus and patience. Calm serenity instead of frustrated rage. (The keyboard will last longer that way.)

I loved the story about Ding cutting up the ox. One thing not mentioned kept coming to mind as I read it. He learned the anatomy of the animal because of his respect for the animal. Instead of hacking away as if it were an inanimate object, he respected (maybe subconsciously) the ox's life force, even though it had left the body. Ding treated the ox's body as he may have done preparing a loved one for burial. It was a beautiful story. Thank you, Alvaro.